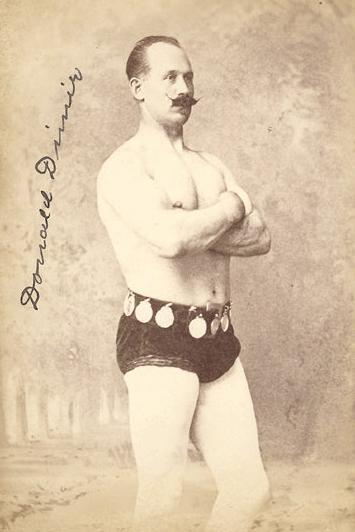

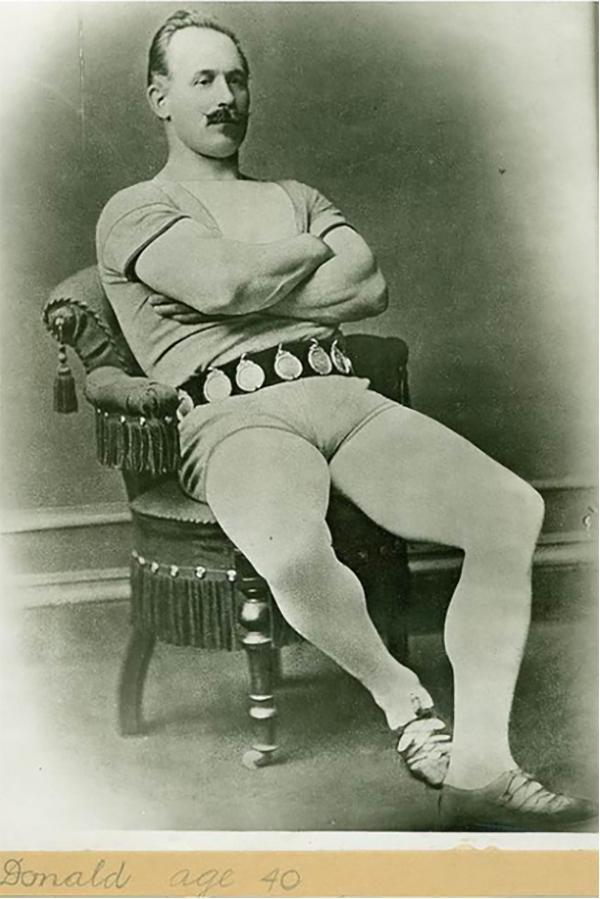

Things find their way to the Stark Center in many different ways. Some items are donated by organizations that reach out to us, as Sports Illustrated did when they were looking for a home for their Olympic archives. Others are donated by individuals such as Irish legend Jack Shanks, who recently sent us the lifting belt and tank top he wore in 1972 when he became the first man to lift the Dinnie Stones after Donald Dinnie himself (read more about Jack Shanks and his lifting belt by clicking here). Other books and archival items are here because Terry and I—and now just I— personally purchased them in order to save them and make them available to scholars, as we did with the Milo Steinborn Collection back in 2017 (read more about the Milo Steinborn Collection by clicking here). The Stark Center began, of course, because Terry and I were collectors and I still spend time each week cruising eBay, looking at old book sites, and searching for items on various auctions that deserve to be saved. During my years of collecting most of the things I’ve purchased have been pretty mundane. However, in late March, as I was scanning through some auction sites in Britain, I was, as the Brits like to say, gobsmacked (which is more than just surprised, it means “ filled with wonder”) to discover that in the small town of Etwall, in the East Midlands of England, a leather belt that belonged to Donald Dinnie, with 12 medals attached, was going to be auctioned. I couldn’t believe that I’d never heard of its existence since most significant physical culture artifacts—like Thomas Inch’s dumbbell or the belt Louis Cyr was given by Richard K Fox or Apollon’s Wheels—have all remained somewhat in the public’s eye. However, I’ve never heard anyone speak of the possibility that Dinnie’s leather belt with the medals attached—the one seen in so many early photos—still existed. But it does, and since I won the auction, it is now here in Texas.

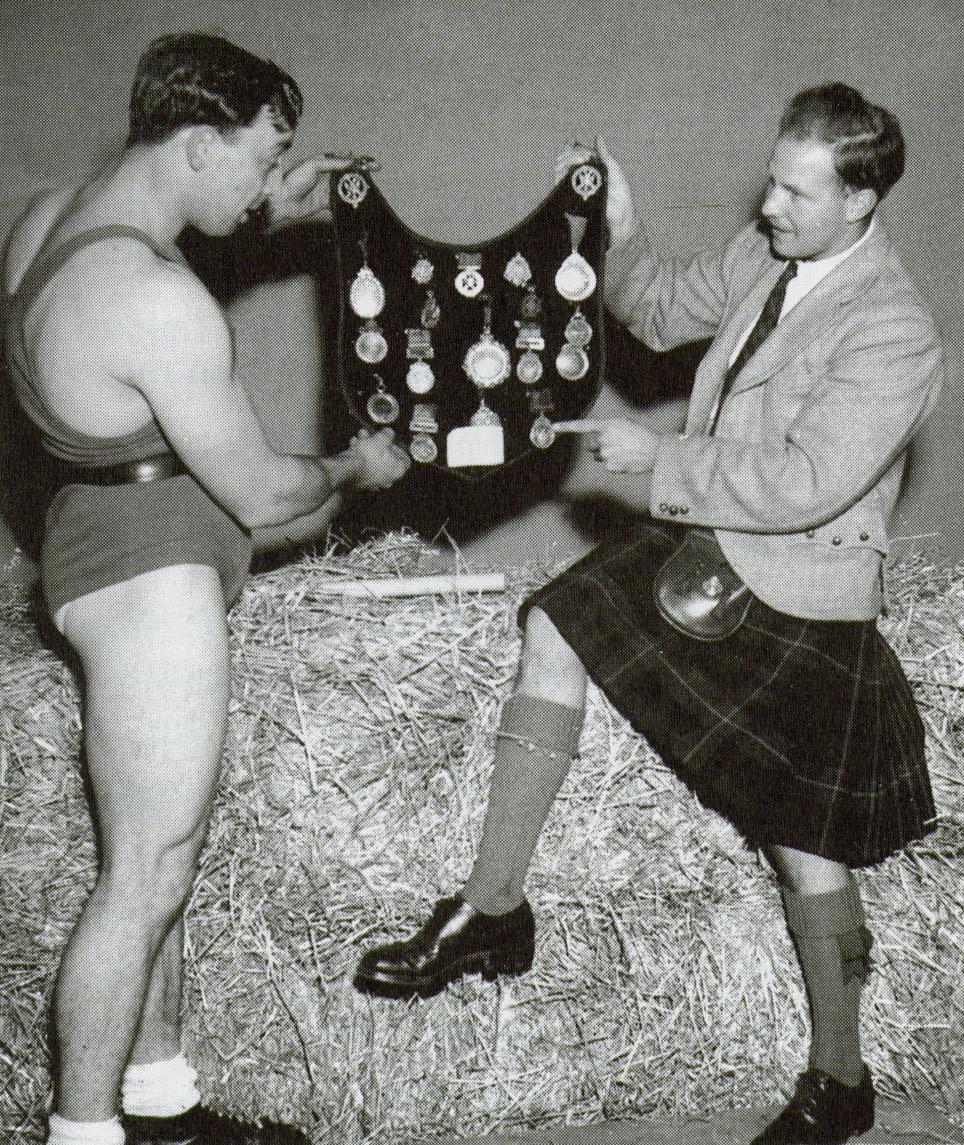

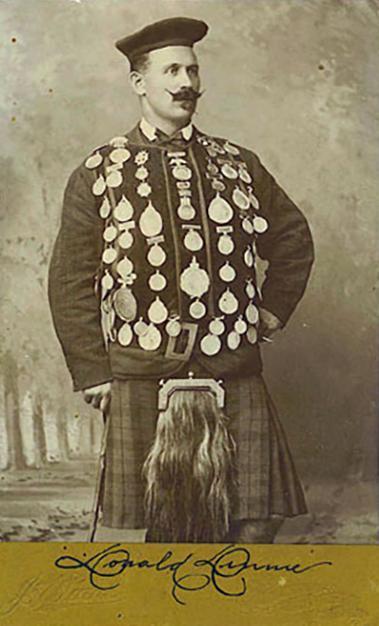

Winning the belt made me realize, however, how little I really knew about Dinnie’s life and so I sat down the next morning, which was a Saturday, and re-read from cover to cover David Webster and Gordon Dinnie’s lovely biography of the great athlete titled Donald Dinnie: The First Sporting Superstar. In their book, published in 1999, I found no mention of “my” belt, but I was reminded of another and far grander belt that was presented to Dinnie in 1900 by some admiring fans after he moved back to Scotland from Australia (where he’d lived for 12 years). “The Champion Athlete’s Belt,” as it says on the main plate, consists of 10 silver plates each with a different image of Dinnie and a record of his achievements in various sporting events. It is now on display at the Aberdeen City Museum. The belt and a collection of Dinnie medals that came with it, can be seen on their website at: https://emuseum.aberdeencity.gov.uk/objects/7623/athletes-presentation-belt. Other than the Aberdeen belt, Webster and Gordon Dinnie report in their book that they were unaware of any other collection of surviving Dinnie medals except for a “breastplate” that had belonged to Donald’s son, Edwin Dinnie. That breastplate being held up by David Webster in the photo below passed through several sets of hands in the 20th century before Gordon Dinnie acquired it. In James Grahame’s 2017 book, Donald Dinnie Uncovered, he also discusses the “Champion’s Belt,” and includes several terrific photos of it. Grahame has also transcribed the engravings on each plate describing Dinnie’s achievements. (See p. 96.)

As for Dinnie’s other medals, there should be hundreds still in existence as Donald competed for 45 years and reportedly won more than 10,000 contests if one adds together his Highland Games individual event victories, his wrestling matches, and his weightlifting contests. We know that many medals were lost in 1882, when a coat covered with medals was stolen from his hotel room in Patterson, New Jersey, while he was appearing at a music hall. But those medals and the many others that decorated his chest in the various cabinet card photographs taken of him, remain undiscovered. Webster and Gordon Dinnie obviously knew of no other medals either, writing to close their discussion of his medals in their book with, “…all that are known to us remain in Scotland.” (p. 119)

Reading this statement made me even more curious about how Dinnie’s leather belt, with 12 medals tacked to it, ended up in an auction so far from the Scottish border. So, I went to the web where I discovered a remarkable, richly-documented biography titled The Life of Donald Dinnie (1837 – 1916) Revisited. This long essay was written by Don Fox, a retired genetics researcher, whose “Don Fox Family and Social History” blogsite is dedicated to his ancestors and life along what’s called Deeside—the forty-mile stretch along the River Dee between Braemar and Banochry. Fox’s essay on Dinnie doesn’t solve the medal question, but it covers his athletic career and then goes into much more detail on the later years of Dinnie’s life than any other source I’ve seen. Don’s meticulous research and elegant writing puts the work of many “professional” historians in the shade, and his examination of the many legal and financial difficulties Dinnie suffered in the later years of his life was a revelation to me. http://donaldpfox.blogspot.com/2017/10/the-life-of-donald-dinnie-1837-1916.html). Like many, I’d primarily thought about Dinnie as “the great athlete,” but reading Fox’s long, nuanced account showed me a different side of Dinnie. And that new knowledge made what I learned from the woman who had put Dinnie’s belt up for auction make total sense.

Jean Barbour is the granddaughter of Duncan Barbour, a farmer whose young life was spent on the Isle of Bute and Cumbrae Island, both located just off the coast of Scotland near Glasgow. Duncan was helping his father run a farm on Cumbrae Island when his father died in 1894. Duncan was then 24 and since the farm they worked was a tenant farm owned by the Marquis of Bute, Duncan decided to leave Bute and strike out on his own. In approximately 1895, he moved from Scotland to the Midlands region of England where he worked on several farms and then bought his own farm near the tiny hamlet of Burton Overy in Leicestershire in 1913. That farm, which is well away from major cities, has stayed in the Barbour family and is currently being farmed by Jean’s brother, John Barbour, and his son, Peter.

In an email answering several questions I’d asked about the belt’s history, Jean wrote, “I really know very little about how the belt came into my family’s possession but what I was told was that Donald Dinnie owed money to my paternal grandfather, Duncan Barbour, and that the belt was given to my grandfather in repayment of the debt in lieu of cash as Donald had fallen on hard times.” She added, “In 1913 my Grandfather moved to a farm in Leicestershire which is still the Barbour family farm.” The belt, she reports, “has been at the farm since then.”

Since receiving this note, Jean, Don Fox, and I have shared several other emails as we’ve tried to figure out when and where these two men might have met and why Dinnie might owe money to Barbour. Don quickly used his research skills and put together a timeline for both men between 1894 and Dinnie’s death in 1916. Based on Don’s work, it appears possible that the two men could have met in late August 1903 at the Highland Gathering on the island of Bute in the town of Rothesay. Dinnie was there as a judge, wearing “his champion belt and principal medals,” according to a local paper. This is undoubtedly a reference to the belt now in Aberdeen and not the much more modest and well-worn belt I purchased at auction. Duncan Barbour’s presence is less certain. But, Don speculates, and I agree, that if Duncan had gone home to Bute to visit his family and/or see his future wife, Hannah Jamieson, who also lived on Bute before they married in 1906, then perhaps this is where he and Dinnie met. We are speculating here, of course, as historians sometimes have to do, and neither Don nor I can confirm that they met—or how a debt could have been incurred—but we intend to keep digging.

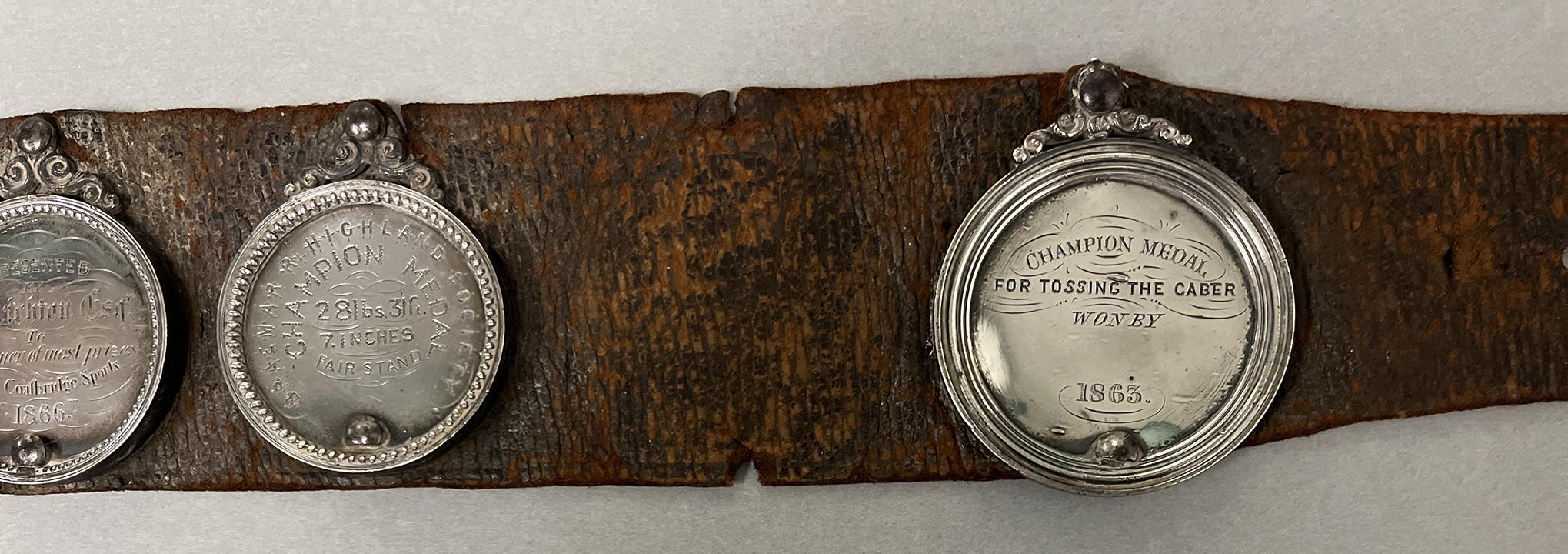

As for the belt, holding it in my hands for the first time was actually quite a remarkable moment. It felt like history. It has been worn so much that the brown leather is soft and pliable like a pair of well-used moccasins. The leather isn’t smooth, however, it’s covered with small cracks and scratches giving testament to its age and use. The tip—where more belt holes should be—has torn away. Without the tip it measures right at a meter as it is 39 inches in length. Since belts normally come with five holes, our best guess here at the Stark is that the whole belt was probably 42 inches in length. It is 2.5 inches wide. The edges of the belt are scraped and frayed, and there are small tears above some of the medals that were probably made by the rings that held the 12 medals to the belt when it was first made. Primitive rivets at both top and bottom of each medal now hold them in place, and so we do not yet know what is engraved on their backs, although when we carefully lift the edges, we can see that there appears to be engraving on all of them.

One of the most noticeable things about the belt, is that there’s a gap, where a medal is missing. Jean Barbour said her grandfather told the family that Dinnie had removed that medal before the belt was given to him, as Dinnie used it to pay another debt. Given the bad state of Dinnie’s finances in his later years, this seems totally logical. As for the medals that remain, here is what is engraved on the front of each of them. I’ve ordered them chronologically, although some don’t show dates or locations on the front side.

- “Champion Prize Medal for Heavy Hammer Won by Donald Dinnie 20th August 1861” No place listed.

- “Champion Prize Medal for Tossing the Cabar Won by Donald Dinnie 20th August 1861”* *(Medal says “cabar” not caber) No place listed.

- “Champion Prize Medal for High Leaping Won by Donald Dinnie 20th August 1861” No place listed.

- “Champion Prize Medal for Putting Stone Won by Donald Dinnie 20th August 1861” No place listed.

- “Champion Medal for Tossing the Caber Won by ____ 1863” No place listed.

- “Presented by D. Crichton Esq. to the Winner of Most Prizes at The Coatbridge Sports. 1866.”

- “Braemar Highland Society Champion Medal 28 lbs. 31 Ft 7 Inches Fair Stand.” No year.

- “Champion Medal for Putting Stone, 16 lbs. 47 Ft. 4 In.” No Date or Place.

- “Champion Medal for Putting Stone, 22 lbs. 42 Ft. 3 In.” No Date or Place.

- “Champion Medal for Throwing Hammer” No Date or Place.

- “Champion Medal for Throwing Hammer 128 Ft 10 In” No Date or Place.

- “Champion Medal for Throwing Hammer 19 Lb. 103 Feet” No Date or Place.

As you can probably tell, I’m still gobsmacked that this unexpected treasure has made it to The Stark Center. Obviously, my own life has been intertwined with Donald Dinnie, David Webster, and the Dinnie Stones and that’s undoubtedly part of why I’ve been smiling so much. I also admit to liking the symmetry of having Dinnie’s belt alongside Jack Shank’s belt in our museum. As a historian, I especially like that these medals appear to all be from such an early time in Dinnie’s career when he was less famous and less likely to be reported on in newspapers. In James Grahame’s book, his “Appendix A” is a list of a hundred competition results in the hammer, stone-put, and ball-put made by Dinnie between 1857 and 1872. (p. 104) None of the distances and weight of implements recorded on these medals appear on his list. They remain a mystery to be solved.

There is no question that the belt is old, and worn and that it was his; his name is clearly written on several of the medals. But the belt is not done with its usefulness. Here at the Stark Center it is already playing a new role. It has inspired me and hopefully others to want to learn more about Donald Dinnie and the Highland Games. In the years ahead, who knows how many others will see it and also be curious to learn more about this man and Scottish sport culture. The belt is also inspiring new friendships. Don Fox and I have found we share many interests and hope to publish something on Dinnie together soon. Finally, the belt has reminded me, again, to be grateful for this life and my friends, and to appreciate how lucky I am to be able to do this work and have such a good life.

Leave a Reply