Like many of my colleagues, online learning has been something of a mixed experience. Entire courses have been completely redesigned, I’m often left lecturing in my spare bedroom and I live, almost constantly, in fear of my two dogs taking over a lecture owing to their indignation with our mail carrier. Students, I’m well aware, are facing all of these pressures and then some. There has been then, a temptation, to simply fall back into tried and tested habits so that I, and the students, can simply survive the semester.

I will admit, somewhat shamefully, that such a thought had crossed my mind on more than one occasion in the weeks leading up to the Fall 2020 term. Being somewhat familiar with the idea of ‘minimum effective doses’, the plan was to create a skeleton syllabus which could change based on how the classes were running in real time. When it became apparent that students were more eager to engage with the content than I realized, it became obvious the skeleton needed to bulk up!

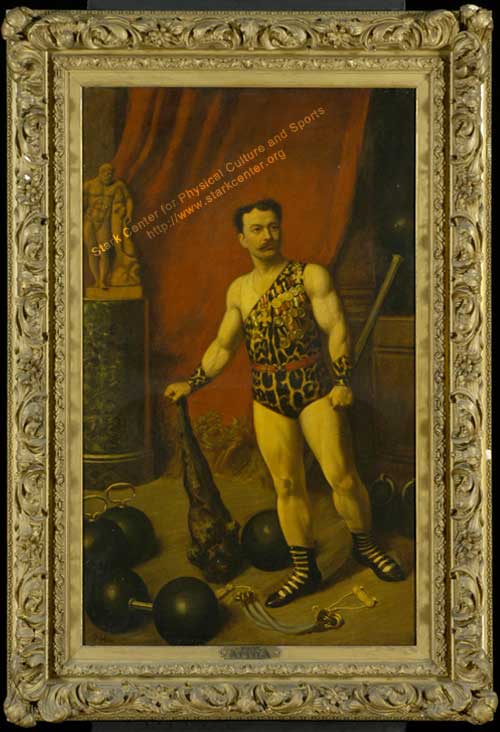

This led me into a somewhat difficult situation of wanting to challenge my students with more work but doing so in a way that was completely accessible online. It was this challenge that was saved by the subject of today’s post, the Professor Attila scrapbook. If you are reading this post, I suspect Professor Attila is a name already familiar to you. Attila (born Ludwig Durlacher) was a professional strongman in his own right, ran a very successful gymnasium in New York in the early 1900s, personally trained several high-profile athletes and, perhaps most famously, is generally regarded as the man who mentored Eugen Sandow to stardom.

Owing to the Stark Center’s prolonged efforts to digitize the history of physical culture Professor Attila’s Scrapbook is freely available through the Stark Website. An idea was soon born. What if I asked students to go through the Scrapbook and create a fictional newspaper article based on what they found? Would they examine the Sandow-Attila court case? Or Sandow’s well publicized strength contest with Sampson in 1889?

The student responses did not disappoint. As I fretted about inevitable technological mishaps – it’s 2020 and nothing can be taken for granted – my students were hard at work devising their articles. The responses, which sadly for reasons of privacy I cannot share, showcased the importance of accessibility and diversity when it comes to physical culture.

The thirty undergraduate students who embarked on this research project undertook remarkably different paths in their research. Some discussed Attila as a pioneer of women’s training based on newspaper articles found in the scrapbook. Others discussed the state of the Vaudeville and Music Hall industry from throwaway comments found in Sandow articles.

Some discussed his entrepreneurial abilities, and a few discussed the art of gym management. Few, and I mean few, actually discussed Attila’s role in Sandow’s iconic weightlifting contest with Sampson in 1889 which launched Sandow’s career. As many historians have explained, Sandow and Attila traveled to London in 1889 to accept music hall performer Sampson’s weightlifting challenge.

Through no small act of personal showmanship, Sandow defeated Sampson, self-adopted the moniker of world’s strongest man and enjoyed a celebrity which would last until his death in 1925. Attila, as David Chapman highlighted in his wonderful biography Sandow the Magnificent, played a large role in the process. That Attila’s scrapbook was replete with articles about Sandow’s victory seemed to substantiate this point.

That my students disregarded, at least implicitly, this story gave me pause for thought. Thus far in the semester, a great deal of work had gone into the tales and stories of the fitness industry – ‘Muscle, Smoke and Mirrors’ as Randy Roach once deemed it – alongside broader issues of race, gender and social class.

Sandow’s ‘rags to riches’ story in which he traveled to London and became a star before advising men on the best means to perfect their body seemed an easy case study for them. Certainly, it is what I would have written about as an undergraduate, and something I often do write about as a professor. I was simply not like my students and that, thankfully, is a wonderful thing.

When students accessed the Professor Attila scrapbook they did so with their interests and ideas in mind, rather than what their professor found the most interesting. Thanks to the class’s diversity of backgrounds, majors and insights, myself and my TA were faced with a smorgasbord of responses rather than thirty near-identical papers about the Sandow-Sampson contest.

This drove home a much broader issue at the heart of the Stark Center’s mission, accessibility. Because my students were able to access the Attila scrapbook online and, in some cases, from different parts of the world, it was possible to refresh thirty fresh research insights. It was, in many cases, a microcosm for the broader work that the Stark’s digitization mission does.

I still remember as a Ph.D. candidate in Ireland, spending hours going through the Stark Center’s various online resources and collecting valuable materials for my research. I had not yet visited the University and did not believe I would have the opportunity to do so. The ability to access materials with ease meant that I could produce my work unimpeded.

In my own case this meant that I could undertake research on the physical culture movement in Ireland. This research, which will thankfully be published in the New Year as a book, marked the first major undertaking on Irish physical culture. Given my own background and research history, I was able to take existing material and use it for a different, new and, hopefully novel, purpose.

When my students returned their papers, I was reminded of one simple truth when it comes to this field. When more people access the materials, we get fresh insights, new voices and new approaches. The semester has not been ideal, but through digital materials like the Attila scrapbook, some value could be found. I’d like to think my students feel the same way …

Leave a Reply