The University of Texas Longhorns boast an athletics program rich in traditions and history that transcends the realm of sports. As we celebrate Black History Month, we’ll take a look at groundbreaking moments and trailblazing efforts of a few of UT’s Black history makers who have left an indelible mark on the Longhorn athletic legacy.

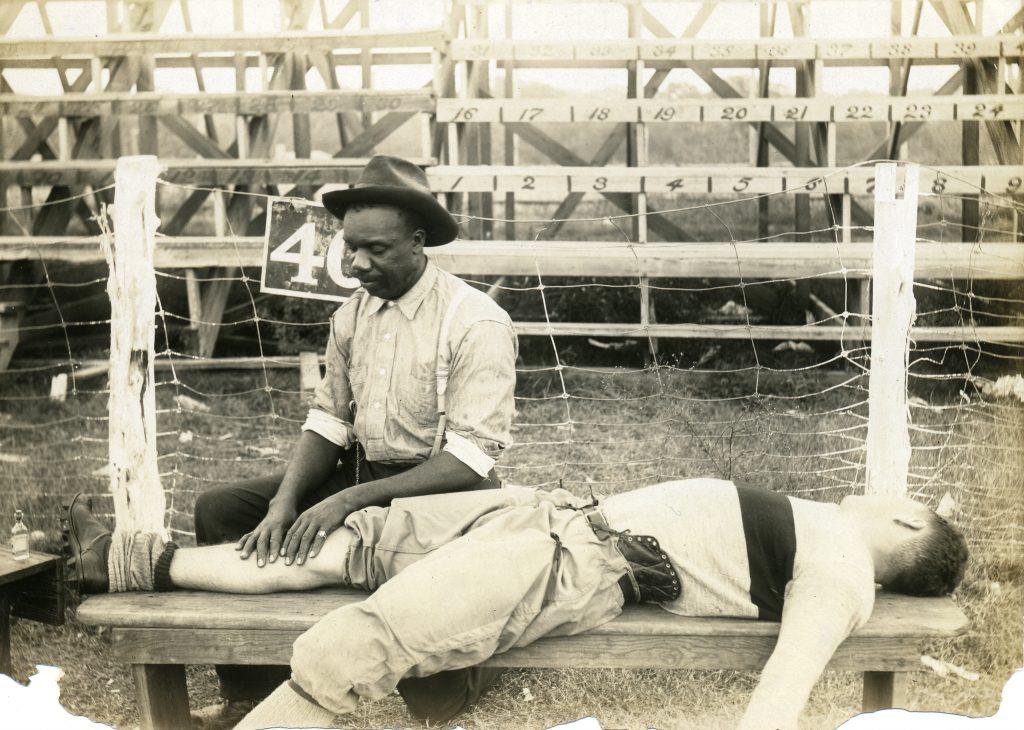

Long before integration at the University of Texas and nearly 70 years before an athlete would break the color barrier, there was a man that would have a huge impact on the UT football program. In 1895, Henry Reeves, an African American, was hired as a facilities janitor at UT. His work as a janitor eventually led to his assignment at the men’s gym, responsible for cleaning and managing the building. The UT football team was in its fifth season when their paths converged. The interactions that Reeves had with the players and coaches would grow over the years as Henry soon began functioning as a water boy, equipment manager, and assistant to the coaches. He built trust with the players and, not before long, he created his own role on the team bandaging cuts, wrapping sprained ankles and knees, and doctoring injuries. For this, he earned the endearing title of “Doc.”

His contributions to the team were widely recognized by the UT community and beyond. The Delta Delta Delta sorority hosted a 1913 dinner and dance for the football squad and Henry was invited. In 1914, in the campus publication, The Longhorn, referred to Henry Reeves as “the most famous character connected with football at the University of Texas…He likes the game of football, and loves the boys that play it.” Journalists would often ask Reeves on the state of the team and his outlook on upcoming games, as he had an uncanny ability to pick the scores. At the Southwestern game in 1914, Henry was asked to lead the crowd in a “Fifteen Rahs” yell, followed by “Texas!” to which he obliged. The crowd responded at the end instead, with “Henry!” The Alcade alumni magazine published his choices for an all-time UT football team, calling it “Henry’s Team” in their publication and it was reprinted in the Cactus. He gained respect and broke longstanding racial barriers in each of these cases.

Henry traveled with the team as far away as Atlanta and Chicago and often endured the humiliation of Jim Crow segregation. When he was forbidden to ride in the same car as the team, they came to his defense. In 1909, when a new gym director tried to replace Henry with a personal friend, the students led a protest and petitioned the Athletic Council, and he was retained. When Henry suffered a stroke on the train ride to the 1915 game in College Station, fans collected over $250 for him a few weeks later at a home game against Notre Dame, which more than covered his medical bills. The Athletic Council voted to award Henry a University pension, the first to an African American. He was respected and well loved by his team, the students, the administration, and the community. In his nearly twenty years on campus, he left a lasting impression and predetermined the integration of athletics, all the while demonstrating a fearlessness of being a pioneer.

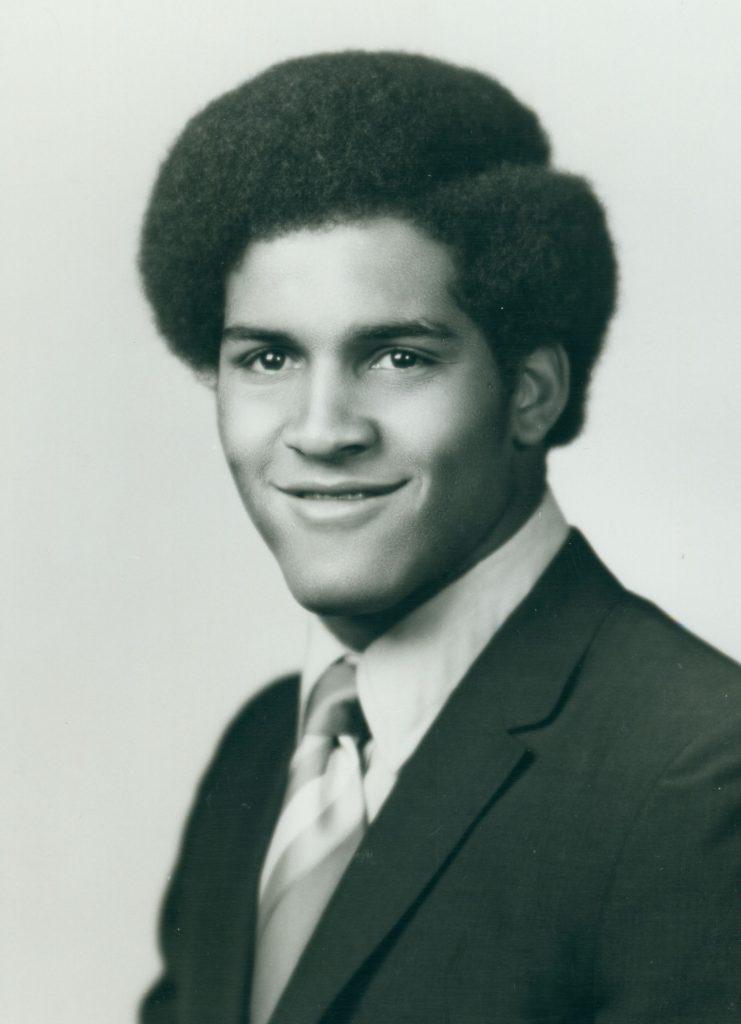

Another trailblazer would come along 66 years later. The University of Texas was gradually integrating its student body, first with graduate students and then, in 1957, with undergraduate admissions of African American students. However, athletics would not begin integrating for another several years. In 1963, Lyndon B. Johnson became President of the United States in the wake of the Kennedy assassination and was committed to a path toward civil rights and freedoms. Johnson’s daughters were students at UT at the time and this could have played a role in the integration of athletics. Eyewitness accounts of freshly painted-over signs above previously segregated washrooms in the football stadium at the 1962 Texas Relays were an indication of times changing. James Means was an Austin High School graduate who planned to attend UT in the fall of 1963 and go out for track. However, athletics was not yet integrated, and he was barred from participating. His mother, Bertha Means, an Austin civil rights activist and teacher, called Frank C. Erwin, a new member on the UT Board of Regents, to protest the fact that James was not eligible to participate in varsity track because he was Black. A few months later, the Board voted unanimously to integrate athletics.

James walked onto the track team his freshman year and immediately made an impact. After already having helped integrate UT athletics, on February 29, 1964, he integrated the Southwest Conference in Amon Carter Stadium in Fort Worth when he led off the UT sprint relay in the 100 & 200 heats at a SWC meet. Despite his impact, he took off the 1965 season because he felt he wasn’t progressing. He returned to the track team in 1966 for the season, earning a scholarship and a letter, the first Black athlete to do so. By his senior season in 1968, his times improved from his freshman year of 10.2, when he ran a 9.5 and barely missed making 1st in the SWC 100 that year. In 1969, he ran on the U.S. Army sprint relay, leading off for Olympians Mel Pender and Charlie Green. The “James Means Spirit Award” is given annually by the UT Track & Field team to a deserving student-athlete in his honor.

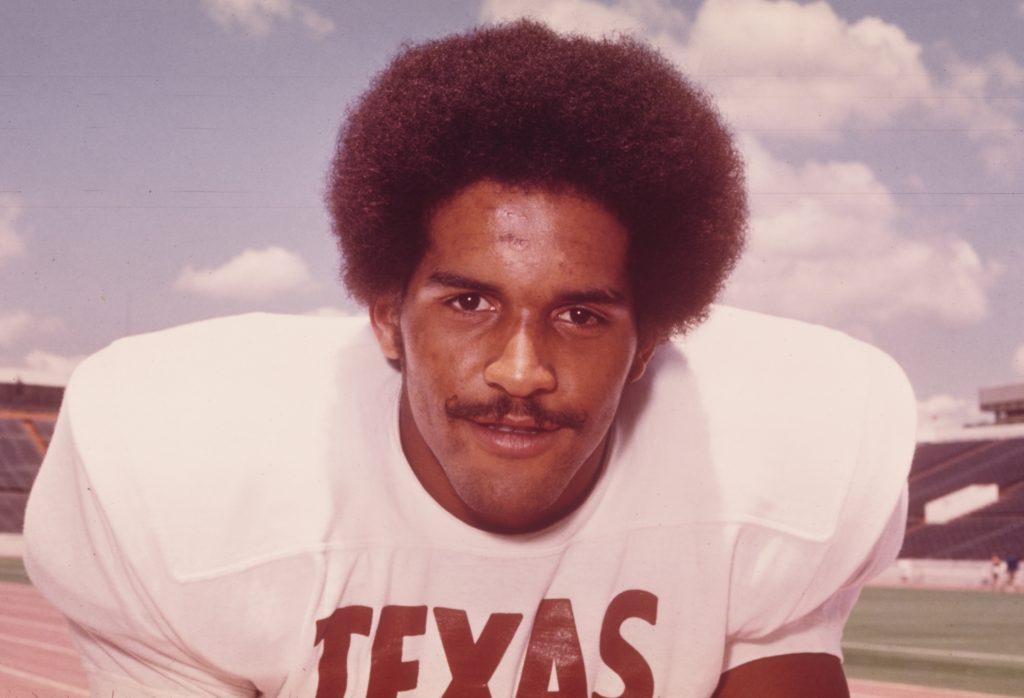

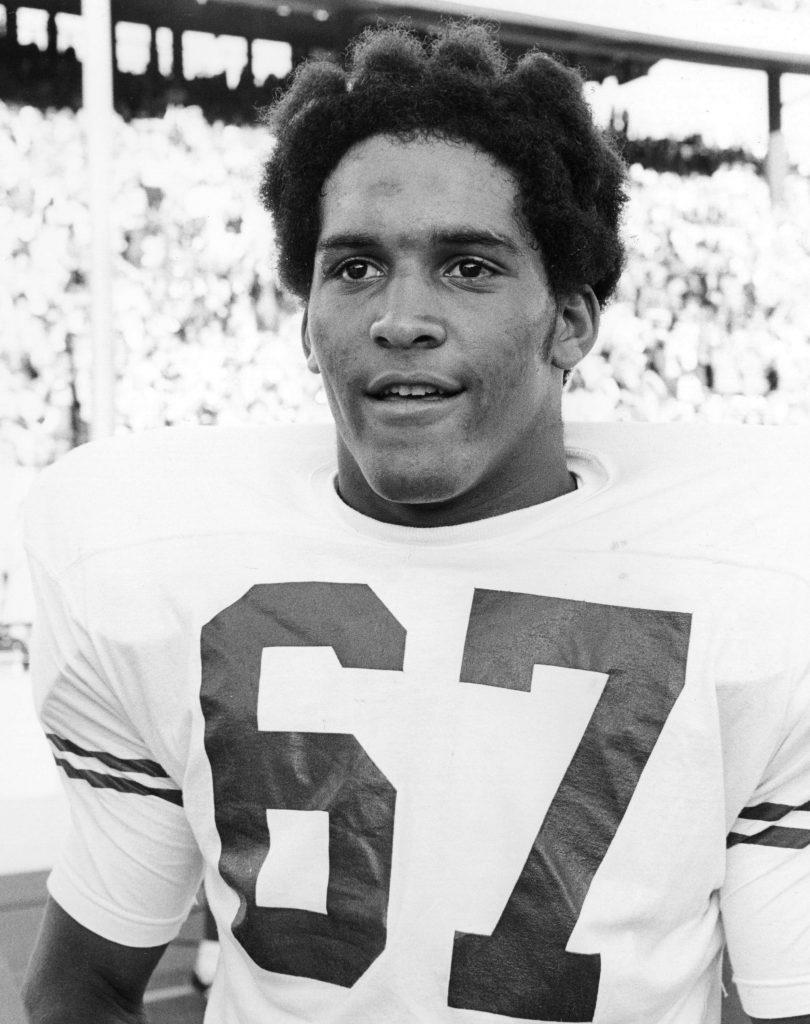

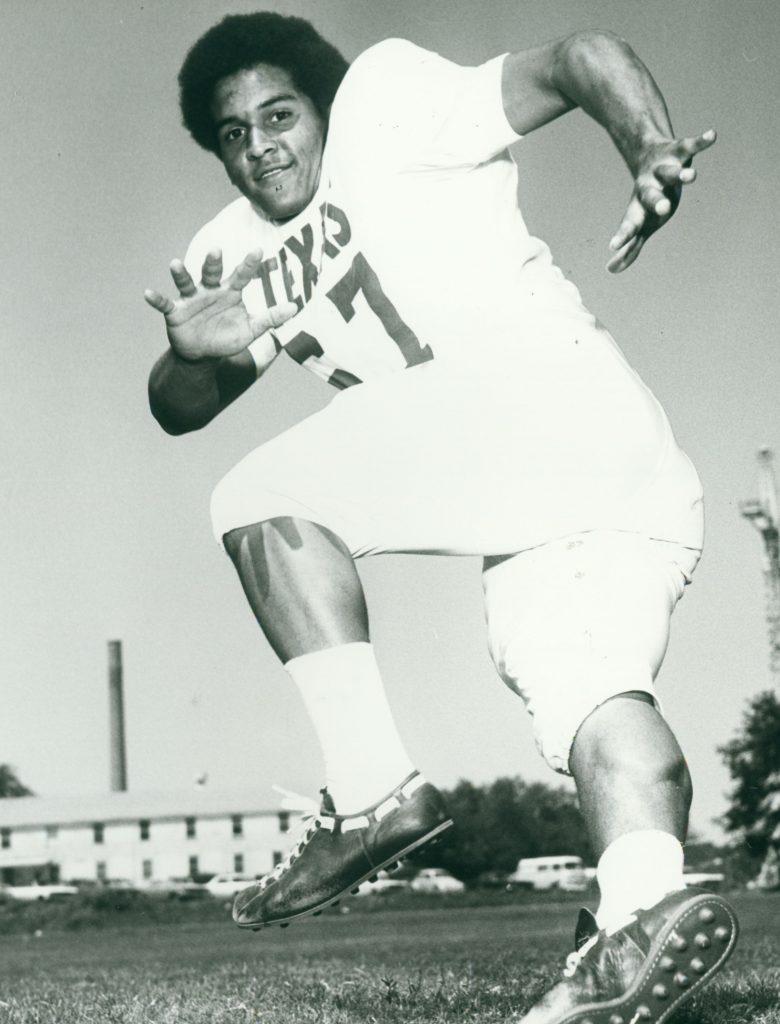

Julius Whittier came to the University of Texas in 1969 as a freshman and was the first African American on scholarship to make the varsity football team. He landed on a campus with nearly 35,000 students and, at the time, only about 300 of them were black. When he was on the freshman squad, he worked out ferociously, making sure that the coaches always took note of his hits. There were a few other African Americans on the freshman team that fought hard to be Longhorns, but Whittier was the first to make varsity. He played offensive tackle for UT’s National Championship teams in 1970 and 1971 and transitioned to tight end for his senior season in 1972. On teams that ran the ball nearly every time, Whittier caught UT’s only touchdown pass in 1972 for four yards on a 38-3 defeat of the Texas A& M Aggies. Julius was a philosophy major at UT and studied dance and moved beyond the football field after graduation.

Julius received sound advice from former President Johnson on a visit to his ranch for lunch with Coach Royal and a few other football players. President Johnson urged him to enroll in the inaugural class of the LBJ School of Public Affairs. He was dancing with the Austin Civic Ballet in 1974 and took time off to enter the LBJ School and earn his master’s degree in Public Policy. He then attended the UT School of Law and earned his law degree in 1980. He moved to Dallas and was hired as an assistant district attorney and spent most of his life as a senior prosecutor in the Dallas County District Attorney’s office. Sadly, Whittier began experiencing behavioral changes that eventually ended his legal career in 2012 that were eventually diagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease. His family filed a lawsuit against the NCAA for negligence when a postmortem examination showed Julius had suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease associated with head trauma. A very tall bronze statue of Julius Whittier stands at the front of the North End Zone at DKR Memorial Stadium in honor of his contribution to the University of Texas as a trailblazer in integrating UT athletics.

On the women’s side of athletics, the situation is a bit more complicated. While at the inception of the University of Texas there were opportunities for women to engage in athletic activities, these were mostly noncompetitive affairs and women were instructed not to seek individual recognition for their athletic skills. In 1900, Pearl Norvell organized the first women’s basketball game at UT which was played in the basement of the old Main Building and basketball emerged as a popular sport among women at UT. Rules were far different than the men’s game and insured that the women didn’t exert too much so as not to hurt themselves. When Anna Hiss came to Texas to run the Physical Training Department in 1921, she launched a Woman’s Program which offered sports clubs and intramural leagues in sports that were deemed “nonaggressive,” including golf, archery, swimming, tennis, and interpretive dance. The prevailing belief at the time was that aggressive, competitive sports were detrimental to a woman’s health. Anna Hiss felt that basketball was unfeminine and potentially dangerous and viewed the sport as an activity for enjoyment only. Needless to say, there weren’t the opportunities that were there for the male athletes in terms of competition, and there were certainly no scholarships offered at all in women’s sports.

In the early 1960s, club memberships started declining as women favored more competitive opportunities. The women petitioned and were able to set up intercollegiate volleyball and basketball teams in 1966 and the UT women’s athletic department was given a budget of $700. The Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) came into being in 1967. In 1972, when Title IX was signed into law and all universities that received federal funds were required to offer equal opportunities for men and women in athletics and academics, women soon found places as head coaches and athletic directors.

It’s difficult to pinpoint when the first Black women were allowed to participate in athletics at UT after integrating the undergraduate student body in 1957. With the AIAW ushering in National Championships and Title IX providing more opportunities to women in athletics, it was only a matter of time before women began receiving athletic scholarships on the 40 acres. 1971 marks the first women’s athletic scholarship (Nancy Hager Hale for golf), Retha Swindell is the first African American to receive an athletic scholarship to UT in 1976 for basketball. She was recruited and played one year for UT’s first African American head coach, Rodney Page. He described her as “poetry in motion with gazelle-like, fluid movements, light on her feet, with explosive quickness in acceleration and leaping.” He had only seen her play defense when he recruited her as high school girls’ basketball consisted of offensive and defensive players who never crossed the half court line.

Retha Swindell was a whole lot of firsts for Texas. She was the first UT player named to the USA Basketball national team, is still the all-time leader in rebounds with 1,759, was named a National Women’s Invitational Tournament All-American (UT’s first), a two-time team MVP, and played professional basketball in Chicago, Milwaukee, and Dallas before the league folded. After her playing career ended, she put her Texas degree in Physical Education to use, teaching and coaching varsity girls basketball for many years in Baytown, Texas at Robert E. Lee High School. In addition, she notably coached one of the, if not the best player in WNBA history, Teresa Weatherspoon. She now works with the nonprofit Legends of the Ball, helping to make sure the WBL receives the recognition it deserves.

“Doc” Henry Reeves, James Means, Julius Whittier, and Retha Swindell are part of the fabric woven into the tapestry that is the history of Texas athletics. These courageous individuals faced many challenges and were trailblazers to making a better path for others to follow. They didn’t set out to be pioneers but through their hard work, ability, and endurance, they persevered. As Retha Swindell said, “It’s not trying to be a trailblazer. Your best becomes the foundation for somebody else.” We honor, celebrate, and thank them for all they did for Texas and for paving the way for future generations of Black Longhorn athletes.

Many thanks to Bill Little, Texas Legacy Support Network, and Texas Athletics.

Leave a Reply