One of the challenges facing historians of physical culture across ages is the issue of biography. Those strongmen and women from the nineteenth and early twentieth-century who did so much to capture our respective attention were, for better or for worse, masters of publicity. It is so often difficult to distinguish between fact and fiction when it comes to the real lives of these performers, and for very good reason.

The often dirty secret of the fitness industry is that aside from being performers and athletes, such individuals were also entrepreneurs. They had stories and products to sell and, as is so often the case, fiction proved more profitable than raw facts. Thus strongmen and women embellished their life stories, told of amazing transformations and sold people on their fictitious lives.

For the historian, be they amateur or professional, this means that the truth is often a rather difficult thing to uncover, especially when dealing with individuals from over one hundred years ago. That is why Edmond Desbonnet and Les Rois de la Force (The Kings of Strength) is such an incredible resource.

Now for those more familiar with Anglophone physical culture, Desbonnet was the Eugen Sandow or Bernarr Macfadden of French physical culture. Born in France in 1867, Desbonnet was an early convert to the then burgeoning physical culture movement sweeping across Europe and parts of North America.

Over the course of his lifetime, he died in 1953, Desbonnet ran La Cultur Physique, a French physical culture magazine, published extensively on the history of physical culture, marketed health devices and also published numerous workouts for his followers. He was an man eternally fascinated and inspired by the pursuit of fitness. More on Desbonnet’s passion for physical culture can be found from an IGH article written by John Grimek about his time with Desbonnet.

The subject of the present post, La Rois de la Force, is testament to Desbonnet’s passion. First written in 1911, La Rois de la Force was Desbonnet’s attempt to chronicle the strongmen and women of his age in an unbiased and measured account. Thus Desbonnet attempted to discuss the actual lives of these individuals rather than their stories.

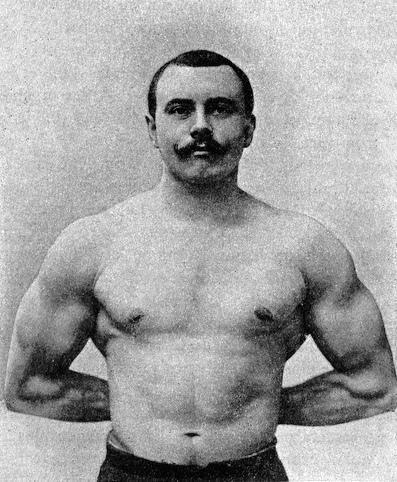

The work, available here through the Stark Center, was one of the first efforts made to chronicle this sort of history and, in effect, marked Desbonnet as one of the earliest chroniclers of the history of strength. In it, readers could learn about the great Sandow, Apollon, Vulcana and many more. For people seeking to first dip their toes in the water of strength history, Desbonnet’s work is an excellent start.

Now obviously, not everyone speaks French and this was a work written entirely in Desbonnet’s mother tongue. Thankfully, David Chapman (the author of Sandow the Magnificent) translated several such articles for IGH many years ago. For interested readers, I would recommend looking at the biographies of Apollon and Hippolyte Triat.

The past year has re-iterated to me the importance of digitized materials like Desbonnet’s Rois de la Force. When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, I struggled to think of how my students would still gain access to the veritable treasure trove which is the Stark Center. Likewise, I know many researchers, who had big plans to visit Texas, were temporarily forced to find new ways of conducting their work.

Being able to access Desbonnet’s work from anywhere in the world – well anywhere with an active internet connection – reminds me that the history of physical culture is truly accessible to everyone. Desbonnet himself would be proud to know that his work, written over one hundred years ago, continues to live on.

Leave a Reply