This is the first of what I hope will be more regular and frequent additions to the Director’s Blog, which I allowed to lapse some months ago due to a combination of other time demands related to the Stark Center, travel, several lengthy writing projects and, of course, procrastination—my old standby. Anyway, I have notes on about 20 new blogs and will do my best to stay on task as we move forward and keep people informed about activities here at the Stark Center. For one thing, we’re fortunate to have recently received a number of wonderful additions to the Center’s various components—the Joe and Betty Weider Museum of Physical Culture, the Todd-McLean Library, and the Sports Gallery. In the first of the new blogs, I want to explain a bit about one of these additions–an artifact from a unique group of primitive weights which are more or less what Barney Rubble might have lifted—and how we acquired it for display in the Weider Museum. So here goes:

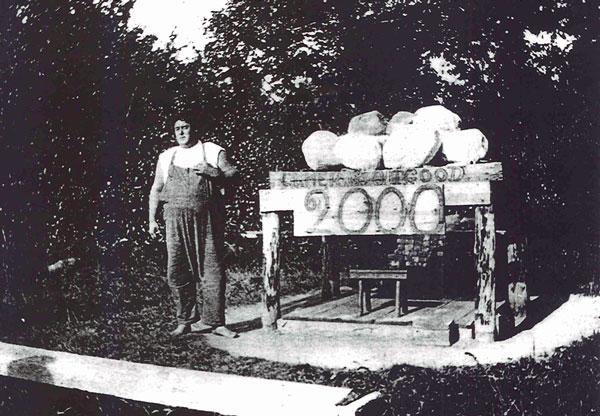

About 12 years ago, the historian John Fair sent us an article about a little known strongman who lived in rural Connecticut and was in his prime around 1900. His name was Elmer Bitgood, and for many decades his legend has been preserved and even enhanced in the area around Voluntown by a group of weights he constructed using rough, round fieldstones made of granite and either connected to a stone of similar size by a heavy iron pipe or, in one case, just a single round stone with a thick iron ring set into the stone for one-handed lifting—like Donald Dinnie’s famous stones. Fair’s article was a real treasure, and with text as well as photos of both Bitgood and his boulders it brought to the attention of iron gamers a man who had otherwise been lost to the world beyond Voluntown. (Apparently, Bitgood also used stones to build a great many smaller weights, but those disappeared in the intervening years by people wanting a piece of history. The remaining weights vary from an estimated 1600 pounds to approximately 250 pounds.)

A contemporary of Louis Cyr, Bitgood, like Cyr, was also a huge man with an equivalently large appetite. Unlike Cyr, however, who traveled widely to earn a good living and undying fame, Bitgood was content to stay at home, work in the woods or on the farm, and lift his crude weights for his own amusement as well as that of his friends and neighbors. Although I had heard of Bitgood from one of my New England friends, I really knew nothing about him until we got Fair’s article, which we published in a 1998 issue of Iron Game History—Volume 5, Number 2. However, once I read the article and saw the photos I was anxious to have a chance to see the massive stones for myself. That chance finally arrived, and so we called Arthur and Mary Anne Nieminen, on whose property the remaining Boulder Bells have rested for decades.

The Nieminens are wonderful folks—real salt of the earth—who must be a lot like the people who muscled a living out of that rugged country a hundred years ago. Arthur is a man able to harness and work a pair of draft horses as well as he can operate heavy equipment, and Mary Anne is a proud protector of the heritage in the area where she has lived her life. When we called them, we explained that we had published the article John Fair had written and that we would really appreciate a chance to see the weights for ourselves. They quickly agreed, and so one day we drove to their property and there the bells were—resting in the grass out in the front yard of the Nieminen’s handsome home. We took a few photos and had a very nice talk with Arthur and Mary Anne, who told us that although many people through the years had tried to buy one or more of the Boulder Bells she had told them no because she believed they should stay in the area where Bitgood made and lifted them. She even told us of her dream to one day find a way to have a small museum built in Voluntown so that the bells could be preserved for future generations.

In the months after our visit we told many people about the old stone weights, and one of the people we told was Greg Ernst, the Nova Scotia strongman who in 1994 made the heaviest backlift in history—5,340 pounds–a lift Jan and I were fortunate enough to witness. Intrigued, Greg and his family made a special stop in Connecticut one year on his way back home from New York City, where he’d gone to attend one of the annual Association of Oldetime Barbell and Strongman dinners organized by Vic Boff. Greg is an “Oldetime Strongman” himself, having won a stone-lifting event in the 1992 “World’s Strongest Man” contest by carrying a 418 pound Husafell Stone for approximately 225’. Greg grew up along the coast in Nova Scotia, which abounds in fieldstones of all sizes, and his interest in stones as well as in math helped him to calculate the approximate weight of the largest of Bitgood’s Boulder Bells.

In the years that followed our publication of John Fair’s article about Bitgood and the visit Jan and I made to see the five weights for ourselves, we continued to build our collection of books, magazines, and photos, but we also began to try to collect important iron game artifacts such as early barbells and dumbbells; anvils; lifting racks; paintings; statuary; and lifting gear owned by strength legends such as Mac Bachelor, David P. Willoughby, Ottley Coulter, Professor Attila, George Jowett, Bob Peoples, Sig Klein, and Paul Anderson. As our collection grew, my mind kept returning to those marvelous stone weights resting comfortably in the yard of Arthur and Mary Anne Nieminen, and when the building of the Stark Center became a certainty rather than a dream I began to think more seriously about how I might acquire one of Bitgood’s weights for display–without doing any damage to Mary Anne Nieminen’s hope that one day a museum could be built in the town where Bitgood lived and lifted.

Finally, after studying photos of the five weights, I noticed that two of the five were very like one another—and very unlike each of the other three weights. Both of the “matched” bells—at about 600 pounds–looked like a much smaller version of the 1600 pounder, and therein lay the key to a plan which would perhaps allow the Nieminens to justify sharing one of those “matched” Boulder Bells with the Stark Center and, by extension, with iron gamers everywhere. The key to the plan was that even though one of the matched bells would be on display at the Center, the Niemenens would still have a match to the one on display at the University of Texas.

So, a little more than a year ago, on our Holiday Season collecting trip to the east and northeast (see the earlier blog I called “There and Back Again.”) to gather in a number of Warren Lincoln Travis’ weights, Alton Eliason’s photos and other ephemera, Bob Peoples’ power rack, and Dr. Charles Yesalis’ steroid papers, we took a day to drive up to Voluntown and lay our plan out to Arthur and Mary Anne. The Nieminens are intelligent, thoughtful people, and they listened carefully to what we had to say. Later, after we had spent a few pleasant hours and eaten far too many of Mary Anne’s cookies, they told us that they saw merit in our plan but wanted to give it some hard thought before making a decision. When the call did come from the Nieminens, they said they had decided that they believed our plan would allow Elmer Bitgood and his Bells to be known about by a great many people, which they thought was a good thing.

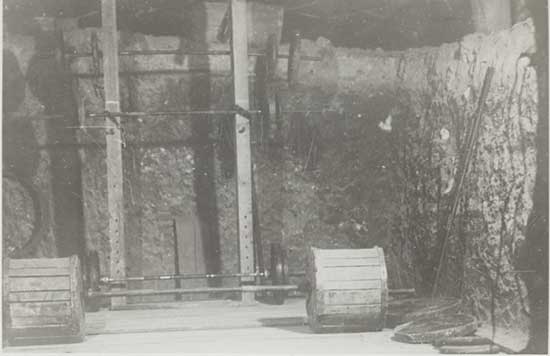

The next thing that had to be decided was how to get the 600 pound Bell from their front yard to the 5th floor of the North End Zone of the Texas football stadium. We offered to pay Arthur to make a heavy crate and then ship it down to the Stark Center as freight, and Arthur agreed, with the stipulation that it would be adequately insured. However, after a period of months had passed we got a call from the Nieminens saying that they had to come down into Pennsylvania for a wedding in the fall and had decided that they’ d just take their recreational vehicle, attach some sort of rack on the vehicle, and drive the Boulder Bell down to Texas. And that’s just what they did. Arthur, as mentioned early, is a very handy man, and he constructed an ingenious rack that can be seen in one of the photos accompanying this blog. The Nieminens explained that they also wanted to personally visit the Stark Center–future home of the Bell—and that they thought they’d enjoy the trip.

At this moment the majestic, daunting weight is resting in a prominent place underneath a large portrait of the bodybuilder Larry Scott, who in his prime would almost certainly have been unable to deadlift it. In fact, the Bell—assuming that Arthur’s method of weighing it was accurate—presents real difficulties since the iron pipe connecting the two boulders is only 20.5” long, which means that a normally proportioned lifter standing 5’9” and weighing 200 pounds would be uncomfortably compressed while gripping and attempting to deadlift the connected stones. Conversely, a 150 pound man who could assume a non-Sumo deadlift position would have to be uncommonly strong to be able to raise such a stiff and unbending weight. (At the “Legend” level, I’ve been thinking of giving a prize to the first person able to lift the Boulder Bell six inches or so using only one hand. Without straps.)

In any case, the great old weight will have a place of honor inside the Weider Museum of Physical Culture when we open later this spring, and the many thousands of people who will see it in the coming years will have Arthur and Mary Anne Nieminen to thank. Plus, of course, Elmer Bitgood.

In any case, the great old weight will have a place of honor inside the Weider Museum of Physical Culture when we open later this spring, and the many thousands of people who will see it in the coming years will have Arthur and Mary Anne Nieminen to thank. Plus, of course, Elmer Bitgood.

Leave a Reply