For whatever reason, hands and hand strength have always fascinated me. Perhaps it began with seeing my maternal grandfather, Marvin Williams, break the shell of a native pecan by the pressure of the thumb and forefinger of one hand—a truly difficult stunt. In any case, my fascitation blossomed in my late teens and early 20s as I ploughed through the extensive collection of magazines about strength training assembled by my friend and mentor Professor Roy “Mac” McLean. In the pages of magazines like Strength, Strength & Health, Iron Man, and Muscle Power I became acquainted with men like Thomas Topham, Louis “Apollon” Uni, Louis Cyr, Cyclops Bienkowski, John Grunn Marx, Charles Vansittart, Warren Lincoln Travis, and Ian “Mac” Bachelor; and I was thrilled by fictional characters like Captain Larsen in Jack London’s book Sea Wolf who could crush a raw potato into pulp with one hand, or the dentist in Frank Norris’s novel McTeague who could extract teeth without forceps, or even Doc Savage who could do all sorts of amazing things like pulling a rifle slug out of a door frame, examine it briefly, nod knowingly and say, “Ah, a .577 Nitro Express.”

No doubt this interest also played a large part in my greater-than-normal interest in practicing feats of hand and wrist strength myself and in the pride I felt when I could bend a particular piece of iron or close a particular gripper. The interest also manifested itself in 1965 when I wrote a two-part article on the subject in Strength and Health, called “Mighty Mitts,” and it rose up again earlier this year when I decided to create a contest devoted to grip strength—also called “Mighty Mitts”–and to use the contest as a sort of “appetizer” for the Arnold Strongman Classic Jan and I have directed in Columbus, Ohio for the past ten years.

For all these reasons and many others besides, I cherish several special “hands” that are now part of the collection which will soon be on display at the Joe and Betty Weider Museum of Physical Culture, which is a central aspect of the Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports. I received the first of these gifts approximately 30 years ago as a present from Jan, whose own hands are famously strong and may one day be discussed in detail in this electronic venue. Jan and I had seen the future gift at the Yerkes Primate Center in Atlanta one day when were the guests of Dr. Terry Maple, who was at that time a Professor of Psychology at Georgia Tech and a member of the Board of Directors at the Yerkes Center. Dr. Maple had read an article about Andre the Giant I’d just published in Sports Illustrated and, as an authority on the “Great Apes,” wanted to talk about the physical comparisons I’d made in the article between Andre and a typical adult male lowland gorilla—a “Silverback.” These talks blossomed into a friendship, and one day when Jan and I were in Atlanta Dr. Maple offered to take us into areas of the Yerkes Center which were not normally open to outsiders. In any case, during our visit we saw displayed in a glass case plaster copies of the hands, feet, and head of what was said to be a famous zoo gorilla, and I was mesmerized by them, especially the massive, impossibly thick hands.

Seeing these casts, and hearing me talk about them later, Jan decided to some secret research. What she learned was that at the time of the gorilla’s death, the taxidermist who had been hired to prepare a full-body mount for a museum made a mold of the hands, feet, and head and then made four “sets” of plaster casts. One set went to the British Museum of Natural History, one to the Yerkes Center, one to a man in Hollywood who specialized in making masks for horror movies, and the final one the taxidermist kept for himself…that is, until Jan convinced him to sell a set to her so we could add it to our collection of oddities. Without question, it was one of the most unusual and satisfying gifts I’ve ever received, and I keep the hands on a desk in my office so that I can see them every day. They’re something to behold, especially up close, where you can see the whorls and lines on the hands and the striking similarities between those monstrous mitts and the hands of even the largest of men. (In an effort to provide full disclosure, I have to confess that from time to time, when I have visitors in my office who know a little bit (but not too much) about the back ground Jan and I have as competitive lifters, I’ve answered the inevitable question, “My God, whose hands are those?” by saying matter-of-factly that during Jan’s lifting career she took massive amounts of every possible muscle- and strength-building drug, including Growth Hormone from gorilla cadavers and that her hands grew to an enormous size as a result. My visitors usually grow quiet at that point, and then say something like, “Wow, that’s really amazing. Are her hands still like that?” Sometimes I’m able to carry on down this well-worn path for awhile longer but I can never keep it up for too long before either exploding or seeing Jan’s scowling face peering around the door of my office.)

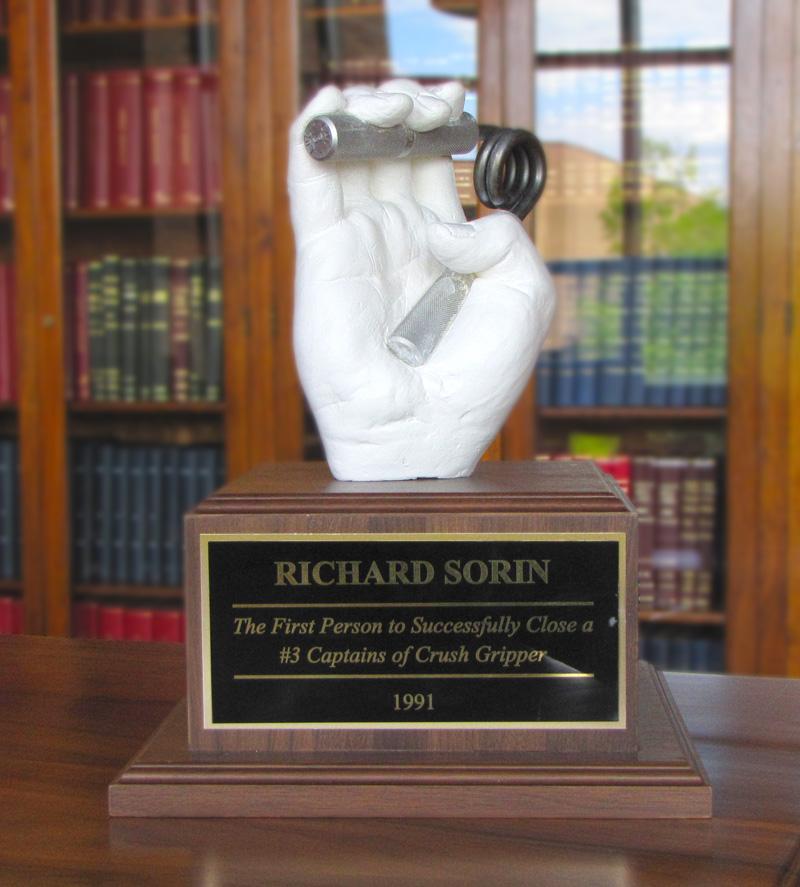

A much more recent—albeit no less treasured—addition to our collection came to me as the result of a conversation with Richard Sorin, a bona fide legend in the world of hand strength and the founder/owner of the well-respected equipment manufacturing company, Sorinex. I’ve known Richard for a very long time, but over the last decade or so we’ve grown much closer as he has helped us with the Arnold Strongman Classic by providing custom-made, extremely heavy duty pieces of equipment for the Arnold Strongman Classic—pieces such as the Heavy Yoke, on which our Strongmen have run with over 1100 pounds across their shoulders, and the Circus Dumbbell, which in 2010 was loaded to 227 pounds. And over the last year or so he and I worked hand in hand, pun intended, on the new Mighty Mitts contest we launched this past March. In one of our dozens of phone calls about the show, he asked me how the Stark Center was coming and I explained that we were gathering as many unique artifacts as we could so that our museum displays would be both memorable and informative. I told him that we had artifacts from a number of famous iron gamers—people like Paul Anderson, Mac Batchelor, David P. Willoughby, Vasily Alexeyev, Sig Klein, Joe Weider, Bob Hoffman, Pudgy Stockton, Bill Kazmaier, Jill Mills, and so on—and I then told him that Jan and I would both be very honored to have something that represented his role in the game as a true Grandmaster of Grip. “Think about it,” I told him. “You’re a genuine pioneer and anything that you’d be proud to have represent you we’d be proud to display.”

Some two weeks later Richard called and said he had an idea about an artifact, which was that he’d use a “Number Three” V-shaped gripper, put it in his hand, close it just a bit, and have a local artist make a single plaster copy of his hand squeezing the original #3 gripper. (Metal grippers of this type were first made by Warren Tetting and sold by Iron Man magazine, and are now numbered from 1 through 4.) “What do you think?” he asked. Well, since he’s the very first person to have closed a #3, a feat he accomplished back in 1991, I told him straightaway that I thought his idea was brilliant. Richard then set about the task of having a mold made so that the cast could be fabricated. As things turned out, it was an arduous process—not as bad, perhaps, as the month-long ordeal Eugen Sandow endured over a hundred years ago when a famous plaster cast concern in London made a full-body cast of the renowned strongman/bodybuilder, but plenty bad enough. For one thing, in order to make such a cast of all or part of a live human being, the part being “captured” must be held completely still for a substantial period of time. In this case, Richard had to pull the handles about an inch toward full closure and hold that position for at least ten minutes. He said it was a great deal harder than he expected it to be, and that the tips of his fingers were badly discolored by the experience and remained very sore for a week.

Nor was that the project’s only problem. The second problem occurred after the cast was essentially completed. As the artist was moving and cleaning the cast it slipped out of his hands, fell to the floor and, being made of plaster, shattered—as did Richard, almost. However, rugged old boy that he is—he submitted to another ten minutes of hell holding the historic implement partly closed so that the plaster could once again set. As before, Richard’s hand was taken off active duty for a week, but this time the artist handled the cast much more carefully, no doubt concerned about what those terrible hands—especially both of them together—might do to his person. Anyway, once Richard had the cast safely in his office he made a special case for it and presented it to me in Columbus in March along with all the other toys he usually brings.

Our most recent gift came very unexpectedly and was hand-delivered (sorry…can’t help myself) by Dr. Kenneth Cooper, the renowned physician who in the late 1960s made a noun out of an adjective and created a new word—“Aerobics.”

The reason Dr. Cooper visited the Stark Center was that we had invited him to attend the April 23rd opening of the Weider Museum. We also wanted to pay public homage to him and to let him see a “super-graphic” of his image on our “Wall of Icons.” I first met Dr. Cooper way back in 1966 in San Antonio at the military base when he was doing the basic research which led two years later to his ground-breaking book—Aerobics—a book which inspired a generation of Americans to get off the couch, put on their running shoes, and get healthy. In 1966 I had just finished my Ph.D. at the University of Texas and was in charge of the physical training program at the Gary Job Corps Center in San Marcos, Texas, which is between Austin and San Antonio. Dr. Cooper wasn’t famous quite yet, but I had heard about his work and had made an appointment with him to determine whether his research could help us increase the overall fitness of our hundreds of Corpsmen.

At the time of my trip to San Antonio I was the current national powerlifting champion in the superheavyweight division and weighed approximately 335 pounds—and this was long before the NFL, college football, and even high school ball were overrun, literally and figuratively, by men and boys who weighed over 300 pounds. I’d said nothing about my sports background to Dr. Cooper since it didn’t seem important in the context of our meeting, but perhaps I should have anticipated how surprised he seemed to be by my appearance when I lumbered into his office and we shook hands. After a few pleasantries he asked me if I was an athlete of some sort and so I explained about my competitive lifting, and that many of the Corpsmen under my care were doing progressive resistance exercise. At that point Dr. Cooper stated, in a non-confrontational way, that he believed the Corpsmen would be better off staying away from the weights and concentrating on a running program. I didn’t agree, of course, and asked him to explain in more detail, which he did. Although we spoke about the subject at some length, his basic position was that any extra flesh—muscle or not—developed as a result of heavy resistance training just made more work for the heart and circulatory system and should therefore be avoided.

During our friendly, but spirited, conversation he asked me if I had the time to go through the battery of tests he administered to servicemen, but I declined by saying that I knew the combination of my bodyweight and the years of training I’d undertaken in order to be able to muster a brief, maximum burst of power had severely limited my aerobic capacity. I added that I could no more follow him around a running track than he could follow me through my daily workouts, but I hastened to say that I planned to begin aerobic training and drop about a hundred pounds within the next year or so because I realized it would be unhealthy to maintain the weight for much longer. In any case, Dr. Cooper seemed to understand and we wished one another well as we parted.

As the years passed, I followed Dr. Cooper’s rocket-like rise and was very happy to note–that as sports scientists around the world began to embrace the same resistance training they had for long rejected–he also began to add strength training to the exercise programs he designed for the thousands of people who flocked to the famed Cooper Clinic in Dallas. As of today, strength training is a key aspect of not only the exercise protocol he recommends but of the exercise program he personally follows. In my case, thanks in part to aerobic training I now weigh a hundred pounds less than I did that day 45 years ago, and I’ve weighed approximately the same thing ever since I retired from competitive lifting about six months after Dr. Cooper and I met.

The next direct contact I had with Dr. Cooper’s work came in 1992 when Clarence Bass asked me to meet him in Dallas during one of his regular trips to the Cooper Clinic for a series of rigorous physiological tests designed to ascertain his strength, flexibility, and aerobic fitness and where he would rank among people his age. Bass–a lifelong advocate of weight training and, a bit more recently, of cardiovascular training—asked me to tag along because he wanted someone to be with him when he underwent the dreaded treadmill test, during which the treadmill gradually increases its speed as well as its upward angle. “I need someone to be my cheerleader,” Clarence explained, and I told him I’d be happy to accompany him so long as I wouldn’t have to follow suit. (His overall results, as expected, placed him in the 99th percentile of his chronological cohorts, and by lasting on the treadmill for just over 28 minutes he just barely missed the 99th percentile in that test, too, which includes many serious runners and bikers.) This experience allowed me to see for myself what a remarkable “campus” Dr. Cooper had developed in Dallas and how many lives he had touched. Without question, Dr. Cooper has had a truly colossal impact on American—and even the world’s—culture. In Brazil, for example, when school age kids train, they say they’re “Cooperizing.”

As for across-the-spectrum impact, consider for a moment that Dr. Cooper’s research has played a central role in determining:

1. That moderate physical activity can reduce the risk of death.

2. That you only need to do 30 minutes of brisk walking five days a week to become moderately fit.

3. That moderate physical activity can increase lifespan by six years.

4. That physical activity is as good as prescription drugs for mild to moderate depression.

5. That physically fit students perform better academically.

6. And my personal favorite… That it’s better to be fat and fit than skinny and sedentary.

Dr. Cooper has also tackled the childhood obesity epidemic, and his FitnessGram sends health report cards home to kids in more than 85,000 schools across the nation. Although Dr Cooper’s in his 80th year of life, he’s still an Energizer Bunny in the field, He’s written 19 books, lectured in more than 50 countries, continues to practice medicine, and still exercises every day.

Dr. Cooper’s on our Wall of Icons because he’s a legendary, ground-breaking, culture-changing, pioneering, myth-busting icon and we could not be prouder that he has agreed to partner with us at the Stark Center, share some of his personal artifacts, and work with us as we tell the Aerobics story by telling the His story.

As for what he gave us, it’s a beautiful bronze sculpture showing his hands cradling and supporting a leaping athlete. The bronze is the work of the noted Texas sculptor Deran Wright, who made molds of Dr. Cooper’s helping hands and, using the lost wax method, created this one-of-a-kind artifact. We were touched and surprised by the gift, and we’re proud to be able to share it with others who may be inspired to lend their own hands to those who need a boost.

Leave a Reply