Twenty years ago, when we began publishing our journal, Iron Game History, we affixed a subtitle: “the Journal of Physical Culture.” We did this because “Physical Culture” is an older and somewhat broader term than is “Physical Fitness,” although the latter is now much more widely used. Sometimes people speak or write about “total fitness” or of becoming “totally fit,” which, when you think about it, is impossible. In fact, it could be argued that the only time a person is totally fit is when that person is dead—at which point he/she is totally fit to be buried, cremated, or used for research. Conversely, the term “Physical Culture” can’t be (mis)used in this way. In other words, it would make no sense to refer to “total culture” or to talk about a person becoming “totally cultured.”

In any case, since “Physical Culture” was the term commonly used a hundred years ago we thought we’d try to do our part to revive it to its former glory. Hence, “Iron Game History: the Journal of Physical Culture.” I’m happy to report that even a casual reader of major newspapers and/or pop culture magazines would have noticed that the term “physical culture” is showing up more and more often. In fact, not too long after Gina Kolata, a longtime writer at the New York Times, spent a number of days talking to us and doing research for her future book at the Todd-McLean Physical Culture Collection —the precursor of The Stark Center—Jan and I saw to our great pleasure that the “paper of record” had initiated a weekly column entitled, “Physical Culture.”

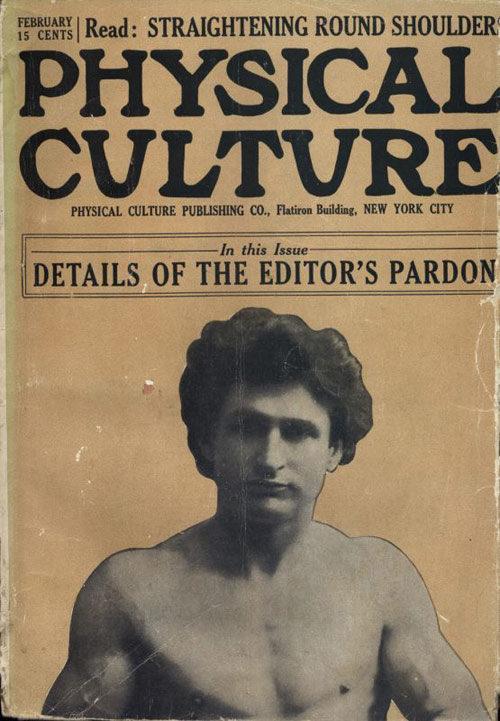

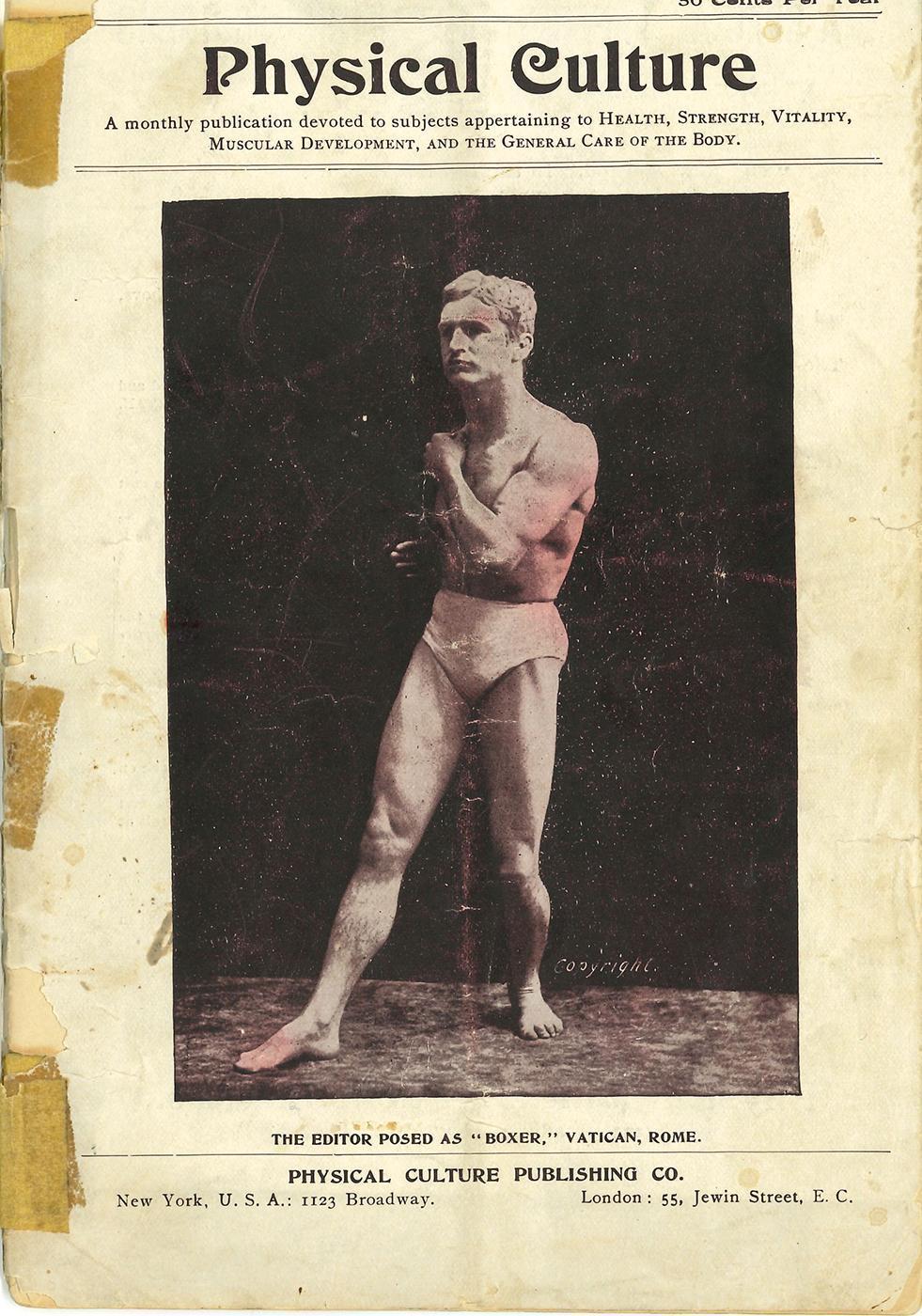

As t o what exactly happened to cause the term “Physical Culture” to fall out of common use we have to look back at the long, fascinating, controversial career of Bernarr Macfadden, who is often referred to as “The Father of Physical Culture.” One of the reasons for this “title” is that Macfadden began, in 1899, a magazine called Physical Culture, and the magazine became so popular over the next several decades that it launched a publishing career which made him, shortly before the Great Depression, wealthier than publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst.

o what exactly happened to cause the term “Physical Culture” to fall out of common use we have to look back at the long, fascinating, controversial career of Bernarr Macfadden, who is often referred to as “The Father of Physical Culture.” One of the reasons for this “title” is that Macfadden began, in 1899, a magazine called Physical Culture, and the magazine became so popular over the next several decades that it launched a publishing career which made him, shortly before the Great Depression, wealthier than publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst.

Macfadden was a truly self-made man of enormous energy who first followed the footsteps of Eugen Sandow and then ran well beyond even the Great Sandow in mining the economic potential inherent in the American public’s interest in self-improvement and physical beauty. Following his instinct, Macfadden held the first contests in the U.S. aimed at determining the “perfect man” and “perfect woman,” and the contests became front page news. Capturing the zeitgeist—the spirit of the times—these contests were wildly popular in some circles and reviled as being pornographic by moralists such as Anthony Comstock in others. Comstock did his bone-headed best to force the authorities to stop the events because the men wore small trunks and the women wore a type of form-fitting union suit, but his bluster only made Macfadden, the contests, and the magazine Physical Culture more famous.

The Macfadden “cause” which played a more pivotal role in the gradual disappearance of the term “physical culture” was his belief that fresh air, alternative medicine, and raw foods were much healthier and safer than allopathic medicine’s reliance on using drugs to treat illness as the way to create health. Primarily because of his monthly broadsides against traditional medicine and processed food, Macfadden was regularly savaged in turn by the food industry, individual medical doctors, and by the very influential American Medical Association, which saw him as a pure-dee Prince of Darkness who was trying to ruin their profession and take money straight from their pockets.

For a long time Macfadden fought the AMA tooth and nail, using his fortune and, especially, the vast power of his magazines, but in the end he was no match for the organizational sophistication and political connections of the AMA.

The primary magazine in Macfadden’s campaign against the AMA, of course, was his original publication—Physical Culture—and as the AMA successfully marginalized the man by calling him a charlatan and a quack they also ridiculed his magazine and even its name. In time, and often helped by Macfadden’s fondness for quirky stunts such as walking to work barefoot, even in winter, people came to view him as unsound, even unbalanced. And as his star faded with the Depression and the relentless onslaught of the AMA–who years later would have to admit that Macfadden had been correct in some of his positions about diet, exercise, and health—the good name of “Physical Culture” faded too. But it’s a fine, sturdy term and we hold with it. Many people advised us to call our facility “The Stark Center for Physical Fitness and Sports” because, they argued, everyone would understand what we were about, it would be easier to attract funding, it didn’t sound so old-fashioned, and so on. Maybe so, but we believe the older term is more accurate. In fact, we like it so much that during a recent assessment of our departmental offerings we initiated a new major called “Physical Culture/Sport Studies”–the only such major in the U.S. Macfadden probably smiled as he looked downward, between his almost certainly bare toes.

Recently, as we were working on some of the text for the museum displays that are now being constructed for The Stark Center, we decided that we needed to provide visitors with a clear definition of the term, “physical culture.” However, when we looked at such major authorities as the Oxford English Dictionary, the Encyclopedia Britannica, and even the consistently misleading Wikipedia—we found each one lacking in one way or another. So we—Jan, actually—took a shot at it and, for now, our working definition is: “Physical Culture is a term used to describe the various activities people have employed over the centuries to strengthen their bodies, enhance their physiques, increase their endurance, improve their cardiovascular health, fight against aging, and become better athletes.” We invite suggestions as to how to make the definition more precise. We’re all physical culturists on the same path doing our best to move, as we say here in Austin, “Onward Through The Fog.”

Read more about Bernarr MacFadden in the March 1991 issue of Iron Game History

-Terry Todd

Leave a Reply