Last summer, I made the decision to expand my academic and professional horizons by pursuing a master’s degree in Sports Management at the University of Texas. The opportunity to learn from leading scholars in the field was too exciting to pass up—even if I do skew the average age of my cohort a bit higher. This semester, I’m enrolled in Ethics in Sport, a course taught by Dr. Charles Stocking. For those unfamiliar with his work, Dr. Stocking is an accomplished scholar who specializes in the history and philosophy of the body, sport, and physical culture from Ancient Greece to the present. His lectures are nothing short of captivating, filled with insights that require deep research to uncover. (For example, I had no idea Socrates was notoriously unhygienic—did you?)

Early in the semester, we examined ancient Greek athletic competitions—chariot races, footraces, and boxing—through the lens of ethical philosophy. We studied thinkers from Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to Kant and Nietzsche, analyzing how their ethical frameworks intersect with the nature of sport. During this exploration, one athletic tradition in particular captured my attention: boxing.

As a tennis player, I’m drawn to the one-on-one, winner-takes-all dynamic of individual competition. Like boxing, tennis is gladiatorial in nature—no ties, no excuses. The roar of the crowd, the mental warfare, the raw physicality, and the isolation under pressure all echo the intensity of combat sports. But what ultimately drew me to boxing wasn’t the competition itself. It was a statue—The Boxer at Rest—housed in the Teresa Lozano Long Art Gallery at the Stark Center.

My initial interest began while researching for a blog I wrote (the Battle Casts collection) on selected pieces from the Battle Collection of Plaster Casts of Ancient Sculpture currently on display at the Stark Center on loan from the Blanton Museum. Then, during one of Dr. Stocking’s lectures, he explained the brutal simplicity of ancient boxing. There were no rounds or time limits, no weight classes, no holding or clinching, and no rules against striking a downed opponent. Fighters continued until one quit—or died. This context cast The Boxer at Rest in an entirely new light.

The original bronze statue is a masterpiece from the Hellenistic period (late 4th–2nd century BCE). It was unearthed in 1885 on the south slope of Rome’s Quirinal Hill, buried in the ruins of the Baths of Constantine. In the excavation photo, the figure appears almost aware—like he had been waiting centuries to be seen again. Scholars believe the statue was deliberately hidden to protect it during the invasions that followed the fall of the Roman Empire.

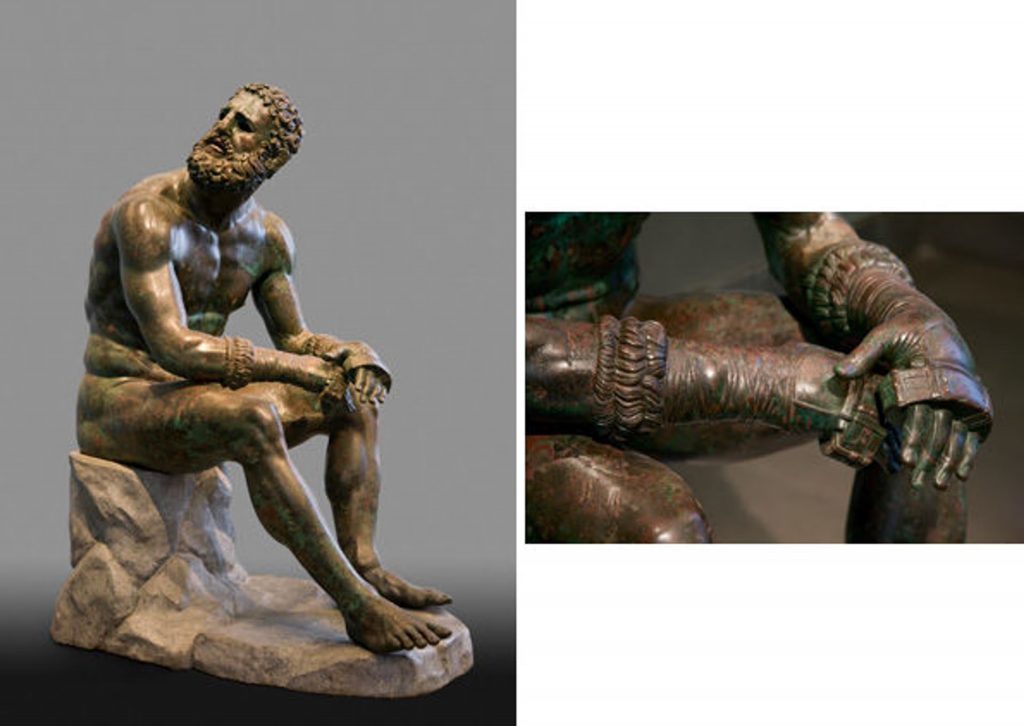

The sculpture depicts a seated boxer, physically and emotionally spent, his arms resting on his knees, head turned slightly to the right, mouth open. He is nude except for his himantes—leather handwraps reinforced with wool padding, designed not for protection, but to maximize the damage dealt to an opponent. His body is covered in cuts, his ears are cauliflowered, his nose broken, and his expression one of exhaustion and pain. A small string, the kynodesme, binds his genitals—an ancient custom meant to preserve modesty and signify athletic discipline.

What captivates viewers most, though, is the ambiguity of his expression. His gaze is weary, introspective, and vulnerable. Some art historians argue it’s impossible to tell whether he’s the victor, the defeated, or simply relieved to have survived. In that ambiguity lies the statue’s power—forcing us to confront not just the violence of ancient sport, but the humanity that endures in its aftermath.

Leave a Reply