On Monday, March 2, 2020, I met my graduate course, The History of the Sport Industry in America, at the Stark Center to talk about a series of readings they’d been assigned that dealt with the business of strength. They were asked to read an article Ben Pollack and I wrote about 1950s gym-chain magnate Vic Tanny, several chapters from Dominic Morais’ dissertation about Bob Hoffman’s marketing tactics to promote the York Barbell Company and, finally, a long essay that Terry wrote about The Arnold Strongman Classic (ASC) in an anthology called Philosophical Considerations of Physical Strength that he also coedited.[1] Terry’s essay describes how he “envisioned” The Arnold Strongman Classic and explains how he wanted to make it different than other strongman-type contests, decisions that meant he and I became centrally involved in the growth of the sport now known as Strongman.

One of the many things I love about the Stark Center is the opportunity it provides for me to show my students’ real artifacts related to the history of physical culture. That day, after sitting at the conference table and getting their reflections on the articles, I took the class back to the Weider Museum galleries to show them photos and strongman implements that I hoped would help make what Terry was talking about more real. As we discussed the evolution of the show and early champions like Mark Henry, Zydrunas Savickas, and Derek Poundstone, whose pictures were on the wall, I walked across the gallery to a group of Olympic weightlifting photos and pointed out a photo of Mikhail Koklyaev from Russia. I used the photo to segue to the fact that I was leaving the next day to go to Columbus and once again direct The 2020 Arnold Strongman Classic. I told them that I knew my involvement in directing and promoting an event such as this was unusual for an academic, but that I’d learned a lot from my involvement with “The Arnold” and that Mikhail Koklyaev played an important role in my education.

When Terry began The Arnold Strongman Classic in 2002, he wanted athletes from all three strength sports (powerlifting, strongman, and Olympic weightlifting) as competitors. Except for Mark Henry, who won the show in 2002, and three-time Olympian Raimonds Bergmanis of Latvia, however, we had not attracted other Olympic weightlifters to the contest. In 2005, Terry heard that the great Russian weightlifter, Mikhail Koklyaev, had begun entering a few strongman contests and he very much wanted Koklyaev to participate in The Arnold. Misha, as he is known to friends, is one of the greatest strength athletes in history with official Olympic lifts of 210.0 kg /463.0 lbs. in the snatch, and 250.0 kg /551.2 lbs. in the clean and jerk. He also totaled 1,007.5 kgs/ 2,221 lbs. in a raw powerlifting contest, and he won many international strongman contests during his distinguished career.

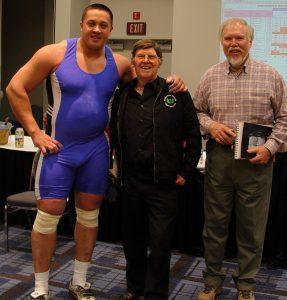

Terry and I first met Misha in September of 2005 at the IFSA World Strongman Championships in Quebec City, Canada. Misha made an indelible impression on both of us when, after being introduced and learning Terry directed the Arnold, he walked across the gym loaded an Olympic bar to 145 kilos/319 pounds and wearing only a tank top, blue-jean shorts and flip flops snatched it effortlessly overhead with no warmup, no lifting belt, and no chalk to help his grip. We were stunned. After witnessing that, it didn’t matter to Terry how Misha finished in Quebec City, he’d already earned an invite to The Arnold.[2]

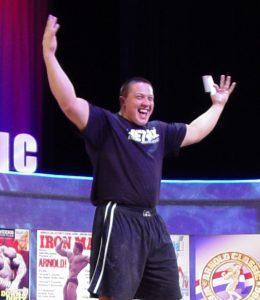

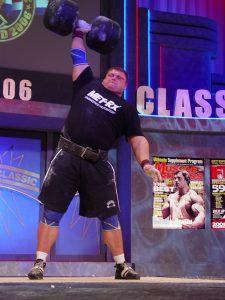

The following March, Misha arrived in Columbus for the 2006 ASC around midnight on the Wednesday before the competition began. To get to Columbus he’d flown from his hometown of Chelyabinsk, near the Ural Mountains, to Moscow and then to Paris where he changed planes to get to Atlanta before his final connection into Columbus. After more than 20 hours of flying, he was upset when his luggage didn’t come down to the carousel and then discovered it was last seen in Paris. Losing your luggage is always hard, but in Misha’s case, it was made far worse by the fact that he’d made the rookie mistake of packing his lifting gear inside his baggage along with his regular clothes. We all figured his luggage would show up the next day, but it had still not arrived on Friday when we left around noon for the convention center for the first day of the ASC. However, with a belt, John and Sarah Fair found for him at a local gym, and a pair of inexpensive tennis shoes that were not at all adequate for the events that day, Misha remained undaunted in the first three events of the ASC—smiling, cheerful, and never once complaining about his loss of gear. The next day, after his baggage finally arrived on Friday night, he again performed well, bowing to the audience and judges as he finished each event, his joy at being in the contest clear to everyone who saw him. On Saturday night, when we did our last event in front of an enormous crowd during the finals of The Arnold men’s bodybuilding competition, he wowed everyone by tying defending champion Zydrunas Savickas in the massive circus dumbbell and taking third place overall behind Zydrunas and Vasyl Virastyuk of the Ukraine.

Following the final event on Saturday night, there was a gathering in the hotel bar that Terry and I left around 1 AM leaving Misha and several of the other strongmen there for what we heard the next day were several more rounds of “celebration.” The next morning, thinking our work was done for the weekend, we had not set an alarm and were sleeping soundly when we heard heavy knocking at about 7:30 AM. Terry groggily made it to the door a few minutes later, only to find a smiling Misha with a gym bag in hand who looked questioningly at Terry and asked, “Do exhibition?”

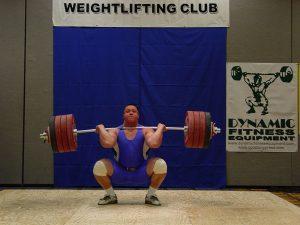

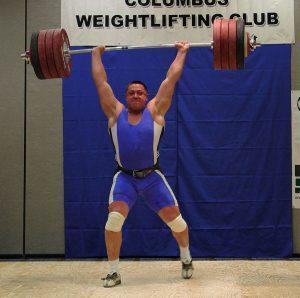

During the negotiations to get Misha to participate in the ASC, his translator had written to Terry that Misha hoped he could also give an exhibition in weightlifting if he agreed to come. Nothing had been said of that after Misha arrived, however, and after finishing the brutal ASC events, and drinking half the night away, we were flabbergasted that he still wanted to demonstrate his skill as an Olympic lifter. But after several hasty phone calls, Terry and I, and our good pals—Kim Beckwith, David Webster, and Steve Slater—were witnesses to the nearly unbelievable sight of Misha Koklyaev—before an audience of about 30 pre-teen lifters at 10 AM in the morning—working up in the clean and jerk to 240 kilos or 529 pounds. It was an Olympic-level performance, done not on the main stage of the Expo but in a small room, with no media, only the five of us, a few weightlifting officials, and the mini-weightlifters. Watching Misha lock out that enormous weight—more than any weightlifter in the world had done in the previous twelve months—after what he had just endured in the Arnold—remains one of the greatest feats of strength I’ve ever witnessed.

Terry understood from the beginning that he/we were doing something unique and historic when he started the ASC, but I view 2006 as my personal watershed in learning to fully appreciate The Arnold. Following his exhibition on Sunday, Misha thanked Terry through an interpreter for making his weightlifting exhibition possible and explained that his decision to come to The Arnold had actually been based on his being able to demonstrate his excellence in both sports. He wanted people to understand, he told us, that he could compete in The Arnold and still have the strength and energy to be a world-class Olympic lifter. As he put it that morning, he wanted “to show what a man can do.” I’ve thought about that statement a lot in the years since 2006 and believe that Misha was actually giving voice to the unspoken value system shared by most of the men who compete at these elite levels, a value system encompassing honor and personal dignity that fuels their training and performance on the platform and is also why they’re seen as heroes and great champions to many.

I’ve been privileged to watch these great athletes “show what a man can do,” and to help create the challenges and events they face when they come to Columbus for 18 years now. And, again this year, with the 2020 contest now over and living its virtual life on the web via Rogue’s brilliant videos, I find myself thinking about the lessons this year’s Arnold taught me. Lessons from Zydrunas Savickas, our eight-time champion, who volunteered to come back and serve as one of our officials so he could give back to the sport; and new lessons from this year’s competitors about comradeship, and personal honor, and perseverance through great pain. The men who compete at the highest levels of Strongman are not on a team, yet they respect and care for each other as if they were. Watching another great Russian competitor, Mikhail Shivlyakov competing after spraining his ankle in this year’s event says a great deal about his courage and personal honor, but so does the way the other athletes cheered for him and encouraged him. And, seeing Mateusz Kieliszkowski and Hafthor Bjornsson finish first and second in the contest thrilled me both for the new levels of strength they’d reached and for their fearlessness in wanting once again to show the world “what a man can do.”

From the front row at Battelle Hall on Saturday evening, as Arnold Schwarzenegger presented a third Louis Cyr trophy to Hafthor Bjornsson, I couldn’t help noticing the tattoo that exhorts “Don’t Weaken” emblazoned on Thor’s 23-inch calf. The phrase had been Terry’s motto and I was reduced to tears when Thor told the audience how important it had been to him personally that Terry Todd believed in him and had given him encouragement. He didn’t have to say that. Thor’s had many men who’ve helped him reach the pinnacle of his strongman mountain, including his remarkable father, Bjorn. That Thor remembered Terry in that way, however, is just one more reason why I regard the men in The Arnold Strongman Classic as special men; men of honor, men of courage, men who even exhibit—more often than one might imagine—what philosophers call excellence. Men who “show what a man can do.”

That’s why, I told my class at the Stark Center back on March 2nd, I feel compelled to return to Columbus each year.

[1] Benjamin Pollack & Jan Todd, “American Icarus: Vic Tanny and America’s First Health Club Chain,” Iron Game History: The Journal of Physical Culture 13, no. 4 (December 2016), 17-37; Dominic Morais, “Strength in Numbers: ‘Strength & Health’ Brand Community from 1932-1964,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Texas-Austin, 2015); and Terry Todd, “Philosophical and Practical Considerations for a Strongman Contest,” Mark A. Holowchak and Terry Todd, editors, Philosophical Reflections on Physical Strength: Does a Strong Mind Need a Strong Body? (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010): 91-129.

[2] He actually finished third behind Zydrunas Savickas and Vasyl Virastyuk of the Ukraine in the World Championships.

Leave a Reply