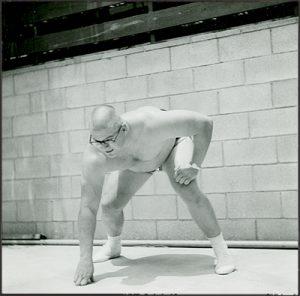

Early in the morning on November 7th, Darrell K Royal—the iconic former football coach at the University of Texas who had fallen under the dread sway of Alzheimer’s a couple of years earlier—died as the result of a fall and a following heart attack. Hearing the news I fell, myself—one of tens of thousands of Texans who had grown to think of “Coach” as Family. Royal and I were classmates of a sort, from the class of 1956. Coach came to the Austin campus in December of that year to take over a stalled football program. He was 32 years old. When he arrived I was already on the campus, having enrolled as a freshman in September. I was 18. I’d begun training with weights three months before, and even though I was an active member of UT’s tennis team the weights had so imparadised my mind during the summer that I almost never missed a workout even though my tennis coach—the former Davis Cupper Wilmer Allison—quickly made it clear that he could tell just by looking at me what I was doing, and that he wanted me—required me, in fact—to stop doing it. But of course I didn’t, although over the next couple of years I kept it quiet and, as I began to occasionally enter weightlifting competitions, I always entered under assumed names—Paul Hepburn and Doug Anderson being my favorites. (Doug Hepburn and Paul Anderson were the top Superheavies in weightlifting at that time.)

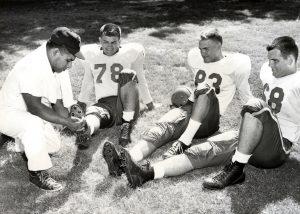

Time on the “Forty Acres” passed for Coach and me, and after two more years he’d put his team on a path toward the dominance they’d maintain over the next couple of decades and I’d decided to put down my racket and focus all my attention on weightlifting. By that time I’d grown to 240 pounds and become larger than every man on the football team but one, who weighed 245. This was only the late 50s, remember, and while I’d been assiduously doing the pulls, squats, and presses that gradually thickened my muscles the players on the UT football team were only running, doing calisthenics, running, and, of course scrimmaging and playing games—plus more running. They grew very little, of course, not having been introduced to the transformative magic of progressive resistance exercise.

By 1960 I weighed approximately 270 pounds. Meanwhile, after a terrific season in 1959 when they went 9-2 and ranked #4 in the nation the UT football team dropped to 7-3-1 in 1960 and fell to #17 by the end of the season. In any case, early in 1961 the word came down one day that Coach wanted me to come to his office. “What could this be about?” I wondered aloud to my training partners, one of whom joked that Coach probably wanted to check on whether I had any remaining eligibility. But of course that was not it. Instead, Coach shook my hand, asked me to sit down, and said he wanted to talk to me, “off the record.” He went on to say that he’d heard about me from some of his players, who were friends of mine, and that he’d watched me play tennis a couple of times. “You’re an athlete,” he said, “and what I’d like for you to do is to tell me why my players should be lifting heavy weights like you do. You probably know that the only weights our head trainer has our boys use are really light—never more than 40 pounds in any lift and not very often.”

I tried not to let Coach see how pleased I was by his question, and as calmly as I could I began to lay out the arguments that I’d absorbed from the pages of the “muscle magazines” I avidly read at that time, especially Strength & Health. I said that I believed multi-joint, heavy weight training was the very best thing his men could be doing as it would increase their bodyweight as well as their explosive power, and I explained that in my own case I was able to jump a little higher at 270 pounds than I could when I began training with weights at about 195. Coach was listening carefully, and so I also told him about the many great athletes who trained with weights—the decathlete Bob Richards, the shot putters Parry O’Brien and Bill Nieder, the baseball player Jackie Jensen, the basketball player Wilt Chamberlain, and the All-American football players Stan Jones, Piggy Barnes, Jim Taylor, and Billy Cannon. “Cannon,” Coach said, shaking his head, “I know they say he’s been lifting heavy for years but when I saw films of him I couldn’t believe his speed. Back when I played all my coaches told me that lifting heavy weights was the worst thing I could do—that they’d tie me up so I couldn’t even comb my hair and that they’d make me stiff and slow. I’d like to have a slow boy like Cannon myself.”

Encouraged, I then went on to explain how Cannon had begun his heavy work with weights with all his high school teammates in Louisiana during the summer before his senior year, and how the team had gone undefeated that fall and Cannon in the spring had won state in the hundred yard dash as well as the shot put—and that he’d gone on and done the same thing at LSU once Coach Paul Dietzel was convinced to put the whole team on a heavy program with the weights. Coach Royal had been listening carefully, but then he really surprised me by saying that he had to be careful making any changes in his team’s training program because the head trainer, Frank Medina, was dead set against lifting heavy weights. “Frank has a lot of support here on campus, and if I pushed for a complete change I know he’d push back. And if we did make a change and we had some injuries or a bad year it would all come back on me.”

I could hear what Coach was saying, as I’d had a run-in with Medina myself a few years earlier when I went to see him about a back injury I’d sustained playing tennis in my sophomore year. The tennis players almost never visited the training room because we knew it was mainly for football, so when I walked in I introduced myself and my problem to Medina, who lacked two inches of being five feet tall. “I know who you are, Todd,” he said with a scowl. “You’re the weightlifter. No wonder you’re having problems with your back. Just look at you. If you keep lifting it’ll just get worse. So stop it and don’t come back with any problems unless you stop lifting those weights.” As evidence that Coach was truly leery of countermanding his head trainer, he didn’t make the change to heavy training until several years later.

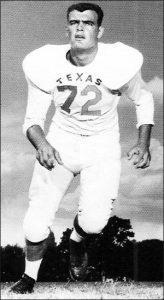

By that time I’d begun work on my doctoral degree, and I was still training hard as a weightlifter and beginning to pay some attention to the new kid on the block—powerlifting. But during that period—probably 1962 or so—I got a call from one of the football coaches asking me if I’d mind taking a look at Don Talbert, an All-Southwest Conference defensive tackle, who was getting ready to turn pro and wanted to gain some weight. I knew about Talbert, of course, as he was one of three brothers, all of whom played for Texas and all of whom were tall and rangy—like big, rawboned cowboys. But when Don came in and I tested him on the bench press, I was absolutely astonished to see that he could only do two or three reps with the Olympic bar and a pair of 45s—135 pounds was almost his limit, and the way the bar moved in and out of the groove on the long way to his long arms’ length was proof that he had no experience at all with this most basic of football lifts. (Later that day Talbert deadlifted 405 pounds, which revealed the sort of good basic strength often seen among working men and non-weight trained athletes.)

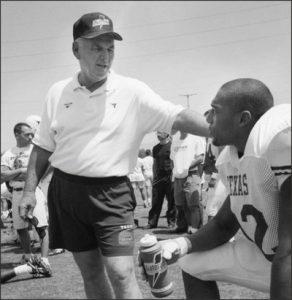

But once Coach made the move to a more modern approach to training football players the Longhorns solidified their status as a perennial power, winning three national team titles during the 1960s. During that period Charlie Craven, a young faculty member who to this day helps with the rehabilitation of injured UT players, had a central role as he gradually introduced heavier weights into the program. Finally, in 1978—shortly after Coach Royal had stepped down as Head Coach and become the Director of Intercollegiate Athletics—UT hired their first full time “Strength Coach,” Dana LaDuc. A former Longhorn field event specialist, LaDuc, who had won the national collegiate championship in the shot put in 1976, began to oversee the weight program for football with the full support of Coach Royal, who spent most of his career as a skeptic of heavy weights for athletes before he realized that, in football, “heavy” was the light at the end of the tunnel.

As for Frank Medina, I interviewed him in 1984 about how things had changed since the days when I’d lettered at UT and he’d been in charge of all of the training done by the Longhorn players. When I visited him at his home that day, Medina had been retired for seven years, but I found him to be an unhappy and–where training theory was concerned–unreconstructed man. As we talked about the sea-changes which had taken place during his 32 years as the Head Trainer, I asked him what he thought of the about face. “We never used weights in my early days here,” Medina recalled, “…and I didn’t believe in it…I still don’t believe in all that heavy stuff. I always said that if God wanted a boy to be bulgy He’d have made him bulgy.”

Having grown fairly bulgy myself by 1964, I left UT in the fall of that year to become managing editor of Strength & Health magazine. I didn’t return for any length of time until 1983, when my wife, Jan, and I came back to UT and began to teach and build our library. Before I joined the faculty, I was teaching at Auburn University in Alabama and writing occasional articles for Sports Illustrated on subjects relating to strength. One of the articles—“Still Going Strong,” published in November of 1970–was a profile of the All-Pro lineman Robert “Bob” Young, who was then starring for the Houston Oilers under Coach Bum Phillips. By that time Young, at the age of 38, was the oldest offensive guard in the National Football League and, two years earlier, had become the oldest man in NFL history selected to play in his first Pro Bowl. (This transformation occurred after Young had spent over a decade as a journeyman guard in the NFL without the benefit of any weight training at all even as it had begun to be used by almost all the down lineman in the league. Finally–spurred to train by the world powerlifting titles being won by his younger, smaller brother Doug—Bob began to work heavy in earnest, and the training plus his freakish natural strength quickly transformed him into the strongest man in football as well as into what Jim Hanifan, his line coach in St. Louis, said was the best offensive lineman in the NFL.) In an odd but interesting way, Young’s college career had touched both my own career as well as that of Coach Royal and, as I was gathering information for the article, I wanted to interview Coach—who years before had won the recruiting war for Young–about his recollection of those long gone days.

When I called to explain my assignment from Sports Illustrated, Coach said he’d be happy to speak to me about “Robert,” adding that his memories were bittersweet. By then Royal had retired as the Texas coach, but he retained an almost mystical reputation on campus because of his remarkable successes as well as his character as a man—a reputation he retained throughout his life and which continues now that he’s gone. When I sat down with him in his office, we exchanged recollections of those early days before the coming of weight training and of how profoundly they had changed the game itself as well as the size and strength of the men who played it.

But when the talk turned to Young, Coach said, “We’ve had a lot of young men here since I came, and I’ve seen some phenomenal athletes, but the only one either here or anywhere else I know of who had the same sort of God-given raw talent for the game of football was Earl Campbell. Robert and Earl had it all—strength, speed, quickness, size, balance, coordination, and an almost instinctive insight into the nature of the game. When we could motivate him I saw Robert do things I never thought I’d see a 17-year-old boy do. None of our varsity players was a match for him one-on-one. He was voted the outstanding freshman lineman in the Southwest Conference, but even then he never played up to his potential. Had he stayed eligible here and gotten serious, there’s little doubt in my mind he’d have been at least a two-time All-American, an Outland Trophy winner, and a million or two dollars richer than he is now. One of the things I’m sorriest about is that we couldn’t manage to keep Robert eligible.”

I told Coach that I suffered some similar frustration myself back then after a weight training friend of mine from Robert’s hometown of Brownwood begged me to come with him to a local gym and watch Robert being tested on the lift my friend revered over all others—the Push Press. I finally agreed to come but I told my friend that if he wanted to really test the basic strength of a teenager who had never trained with weights it would be wiser to test him on the Deadlift, which didn’t require the timing, coordination, and “knack” of a lift like the Push Press. However, my friend wouldn’t be swayed and so we tested Robert’s Push Press –“Not the Push Jerk, by God, the Push PRESS! No bending of the knees after driving the bar off the shoulders!”

Anyway, when we got to the gym and I met Robert, my conviction grew that he had no chance at all to Push Press a heavy weight because his shoulders and upper arms showed no evidence at all of any weight training. He was, however, very thick from his chest down to his thighs—rotund and portly, like a young, well-fed bear. However, as I watched my friend show Robert how to do a “correct Push Press,” and watched Robert began to lift I went from being impressed to being shocked to being absolutely flabbergasted as the bar went up and up and up again—from 135 pounds in fairly small jumps all the way to 300 pounds. Three Hundred Pounds! I have little doubt that many seasoned lifters—especially weightlifters–will be convinced when they read the figures I’ve just written that after all these years I’ve simply forgotten. And some will think I’m trying to add to the Young Legend, since we became close friends later in life. But I saw him do it, and I’ll never forget it.

I should add that there was no “pressing” at all in Robert’s Push Presses. He simply took the bar off of a squat rack, stepped back, bent his knees and then drove the bar overhead so fast that it never slowed down until it was locked out overhead. Perhaps more amazing, Robert never lost his balance. Later, as I thought about what appeared to be a miracle, I realized that Robert had such prodigious explosive power in his legs, hips, and body that they drove the bar over his head and such precise coordination that he could balance and control his body like a seasoned lifter. After having seen what he could do, I did everything I could to convince him to begin heavy training. I even promised I’d pick him up at his dorm, take him to the weight room, and take him back again. But although he went with me a couple of times he was just too interested in sleeping late, eating huge meals, and leaving his dorm in the early evening focused on fun. But both Coach and I knew a puredee phenomenon when we saw one.

The next direct interaction I had with Coach happened in 1984, soon after I joined the UT faculty and began to pay my respects to some of the people who had been here back when I left. The main reason I wanted to talk to Coach was that I already had hopes of creating a place on campus where artifacts of all sorts related to the rich history of Varsity Athletics at UT, particularly football, could be showcased. As a letterman myself I’d always believed that it would be a smart play for UT to build a museum in which it could pay its respects to the hundreds, even thousands, of young men and young women who had put so much sweat equity into the building of the Longhorn brand. (In the spirit of full disclosure, I should add that another one of my reasons for suggesting such a museum to Coach was that I thought it might also be a place where Jan and I could house our growing physical culture collection and share it with others.)

In any case, once I sat down to make my pitch to Coach for such a facility I soon reached the point at which I asked him if he had any items such as letters, photos, and tapes that he might be willing to contribute. At that moment his face clouded over and he began to shake his head. “I’m ashamed to tell you what I have to tell you,” he said, “but back when the time came that I stepped down as the Athletic Director I wanted to clear my office out as soon as I could. So one day I asked my assistant to bring in some big trash cans.” Trash cans. Those words chilled me, and I knew more bad news was coming. Sure enough, Coach went on to describe how he began to pull out the drawers of his long bank of filing cabinets and dump the contents into the trash cans. “I still can’t believe I threw all those letters away,” he said. “Most of them were from a long time ago and lots of them were from players and coaches. By then I had thousands of letters, and many’s the day when I’ve wished I still had them.”

Even so–in the strange way life has of sometimes reaching back, taking hold of a woof out of the past and pulling it through the warp of the here and now so that a solid fabric is made whole again–we were contacted early last year by Jenna McEachren, a gifted writer and good friend of the Royal family. Jenna—who had by then just finished a manuscript of a recently-published book about Coach—explained to us that Edith Royal, Coach’s wife of over 60 years, had a large number of personal photo albums she’d accumulated over the years and that she and Coach might be willing to donate them to the archives of the Stark Center. We of course told Jenna we’d be delighted to see, care for, and display the albums, and we invited her to bring Mrs. Royal to visit the center. That visit began a series of meetings and discussions which led in time to the gift last summer of 29 large photo albums covering the major aspects of the amazing life she and Coach had together. During one of our early meetings I told Mrs. Royal about the meeting I had with Coach in 1984 when he revealed that he’d disposed of his vast collection of correspondence, and that he’d regretted it ever since. “Well,” Mrs. Royal said, smiling, “that was a shame, but thank goodness I’ve always been a saver.”

Here’s how I see this story. Edith understood that even after the passing of the three decades since he emptied his filing cabinets—and even with the late onset of Alzheimer’s disease–Coach would be pleased to know that some of the countless photos taken of him, his friends, and his family would wind up in a facility dedicated to sports and fitness. However that might be, last summer Jan and I drove to the Royal’s beautiful condo overlooking the Hill Country, boxed up those 29 albums, carried them back to UT, and put them in a safe, secure, and climate-controlled part of the Stark Center where they’ll remain until later this year when we mount a photo exhibit featuring this wise, charismatic man who during the 20 years he coached football here had the best record of any man in the country; the respect of US Presidents; and the friendship and love of rowdy, whisky-drinking singers and and songwriters like Willie and Waylon and Jerry Jeff—artists who paid that love forward by sharing the stage with and befriending the long-haired, dope-smoking, creative harbingers of a changing world and, in the process, laying the groundwork for what’s now known from Belgrade to Borneo as the live music capitol of the world.

The foundation of Coach’s fame flowed from his dominance in one of the most violent of sports, but early on he understood that everybody deserves to be treated with respect and that we’d all be better off if we’d just let one another be. One of the many things which speak to Coach’s character is his often-repeated admission that he should have integrated his football team sooner than he did. No one forced him to admit it. But he owned up to it even so, just as he admitted to me a half century ago that when he watched Billy Cannon light the grass on fire he knew that what his coaches had taught him and what he’d taught the players about lifting heavy weights was dead wrong. I felt honored that Coach called me in for a talk that day and I felt honored to share the truth my body told me. Now that he’s gone on ahead—and thanks to Edith Royal’s saving grace–I’m honored to have such a rich photographic record of their life together and honored to have it here, in a stadium which bears his name.

Leave a Reply