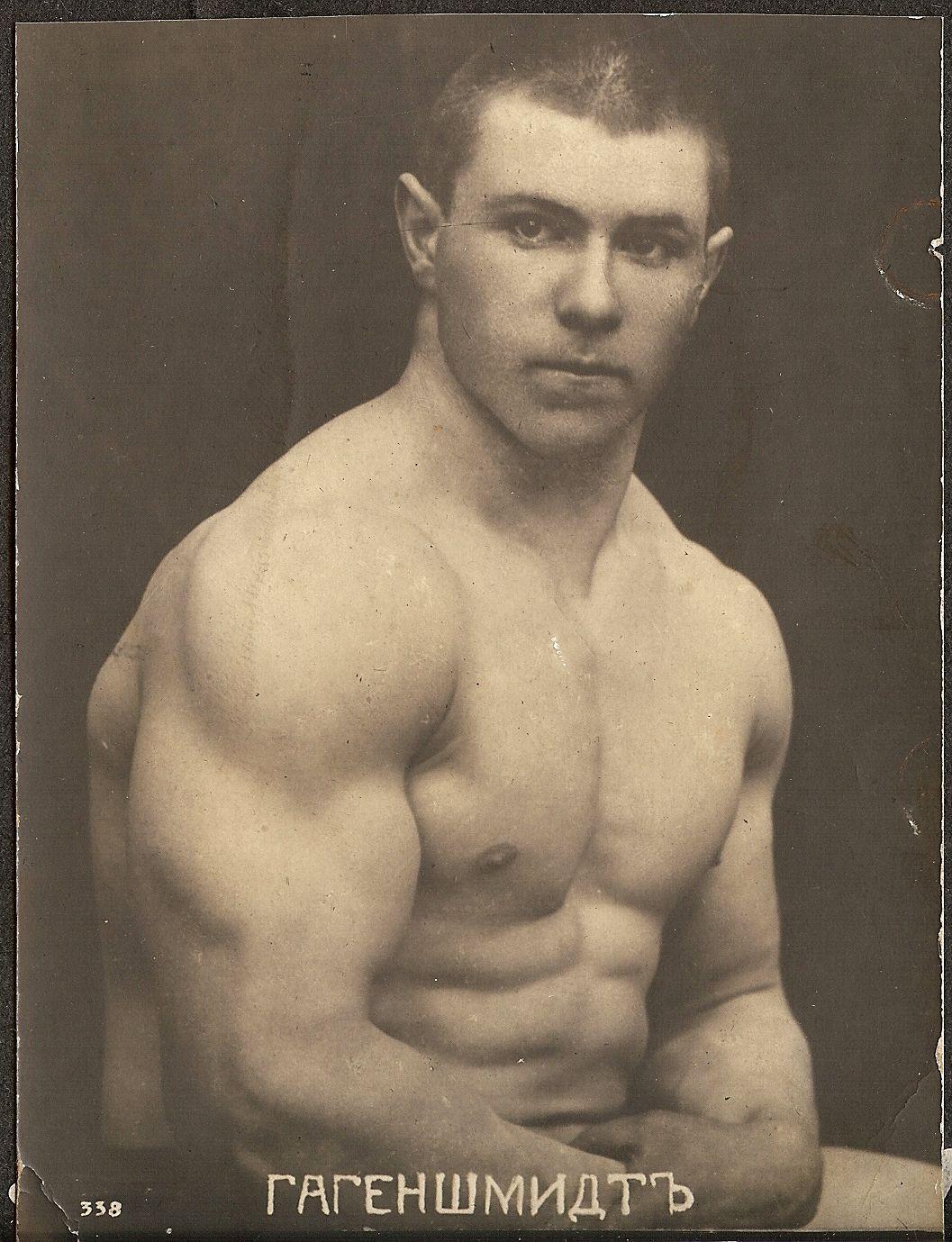

The main point of today’s post is to announce that we have just placed on our Stark Center Research Page a digitized, searchable version of one of our most important documents—the almost 600-page scrapbook owned for decades by George Hackenschmidt, the World Wrestling Champion during the early part of the 20th century. The entire scrapbook is included on our site, and it is very gratifying to the Stark Center team to be able to make this unique artifact available.

Rest assured that we’ll continue in the future to electronically share more of our rare documents so that researchers and fans won’t have to travel to the University of Texas in order to read and study them. Sharing is our raison d’étre—our reason for being. This is not to say that we don’t want people to visit the Stark Center in person to use our research facilities, to examine our old weights, or to enjoy our paintings and sculpture. These things, unlike the personal scrapbook of Hackenschmidt, “The Russian Lion,” are not subject to digitization.

How we acquired the very large and wonderful scrapbook which had belonged to the legendary weightlifter and wrestler and how it came to be digitized and available around the world is a story which began approximately 50 years ago when I met Charles A. Smith, an Englishman who had moved to Austin to work at a public weight training gym owned by his friend Leo Murdock. By that time Smith had gone through World War II in the British Royal Navy, worked as an editor and writer for several of Joe Weider’s magazines, and even lived for a time in Alliance, Nebraska, in unfilled hopes of finding full-time work as a writer with Peary Rader’s Iron Man.

This isn’t the time to tell the Charlie Smith story entire, as interesting and melancholy as it is, but I do need to explain that the friendship which developed back then between me and Charlie—based on a shared love of books, iron, and beer—continued even after I moved away, became an editor and writer for muscle mags myself, and then segued into the life of an academic.

Almost every year after I left Texas I’d come back to Austin to visit my sizable family, and on each visit I’d make time to pay a call on Charlie, who had found work as a juvenile court officer after Leo Murdock lost his gym. Over the years, one of the people Charlie often talked about was his best boyhood friend—Joe Assirati, a lifelong physical culturist from a large London family which by chance included his cousin, Bert Assirati, a prodigiously strong professional wrestler. I never tired of Charlie’s tales about the strength of Bert and the decency of Joe, who later played a large role in the story of Hack’s scrapbook.

When Jan and I finally returned to Austin for good, in 1983, one of the first things I did was to call Charlie, only to learn that his phone had been disconnected. So, later that morning I drove to his house and one of his neighbors told me that Charlie was ill and living with his daughter’s family in another part of the city. When I finally found Charlie’s daughter’s home it was a hard thing to see him so diminished and frail. Even though it was the afternoon he was unshaven, still wearing his pajamas, and sitting in the wheelchair to which he’d been confined after diabetes had cost him most of his lower leg. He did manage a wan smile, and after a while snatches of his witty old self would return every now and again.

During that long talk I told Charlie that I had taken a position at the University of Texas, that Jan and I had brought our growing collection with us, and that I wanted him to visit us on campus as soon as he could. I told him I’d pick him up and bring him home, but he was cool to the idea, citing his lack of mobility and general loss of interest in the world, even the world of weights—to which he had once been among the most devoted of men.

But I persisted and he finally agreed to let us pick him up and take him to UT. To compress a very long story, over a number of visits Charlie gradually became more interested in our many books, photos, and magazines. Finally, rather than simply letting him browse, I asked him if he’d help with the task of sorting and filing the dozens of boxes of clippings that were part of the Ottley Coulter Collection. Charlie then began coming twice a week, and every day we’d push him out to our truck in his wheelchair, load the chair in the bed, and drive him to campus…and then back to his daughter’s home in the afternoon. We noticed that his color was improving, along with his attitude, and before long he asked us to help him move back into his small house.

During his time with us—just as it was in the beginning of our friendship 25 years earlier—Charlie’s favorite topic was his best pal Joe Assirati, with whom he’d stayed in touch through the years. Charlie, who apparently had had a very rough childhood, remained deeply grateful for the way Joe’s family took him in and sustained him.

One day, as he was telling me what a fine stylist Joe had been in the “Olympic Lifts” and how keen a student of the game he was, he asked me if he could bring Joe to the university. “Is Joe in Austin?” I asked incredulously, and Charlie said, “No, but I want to invite him.” When I told him I’d love to meet Joe and to have him see our collection Charlie’s world class smile—which we’d been seeing more and more often—spread across his broad face.

Joe came soon afterward, and both Jan and I were captivated by his knowledge of physical culture, his infectious good nature, and his obvious affection for the man he called, “our Charlie.” We spent many fine hours with these two interesting—but very different—men, and after dropping Charlie off at his home we often took Joe with us to the gym or out into the country for a rambling hike. Physically, Joe was a marvel; his perfect posture, springing step, and great vigor were in stark contrast to Charlie’s improving, but still marginal, health.

One of the things I learned from Joe during his trip to Austin was that he had known George Hackenschmidt in London before and after World War II and that he and his wife had often dined with George and Rachel Hackenschmidt. I found this amazing. Here Joe was, in the mid-1980s, sitting in our offices talking about socializing with a legendary strength athlete who was born in 1878.

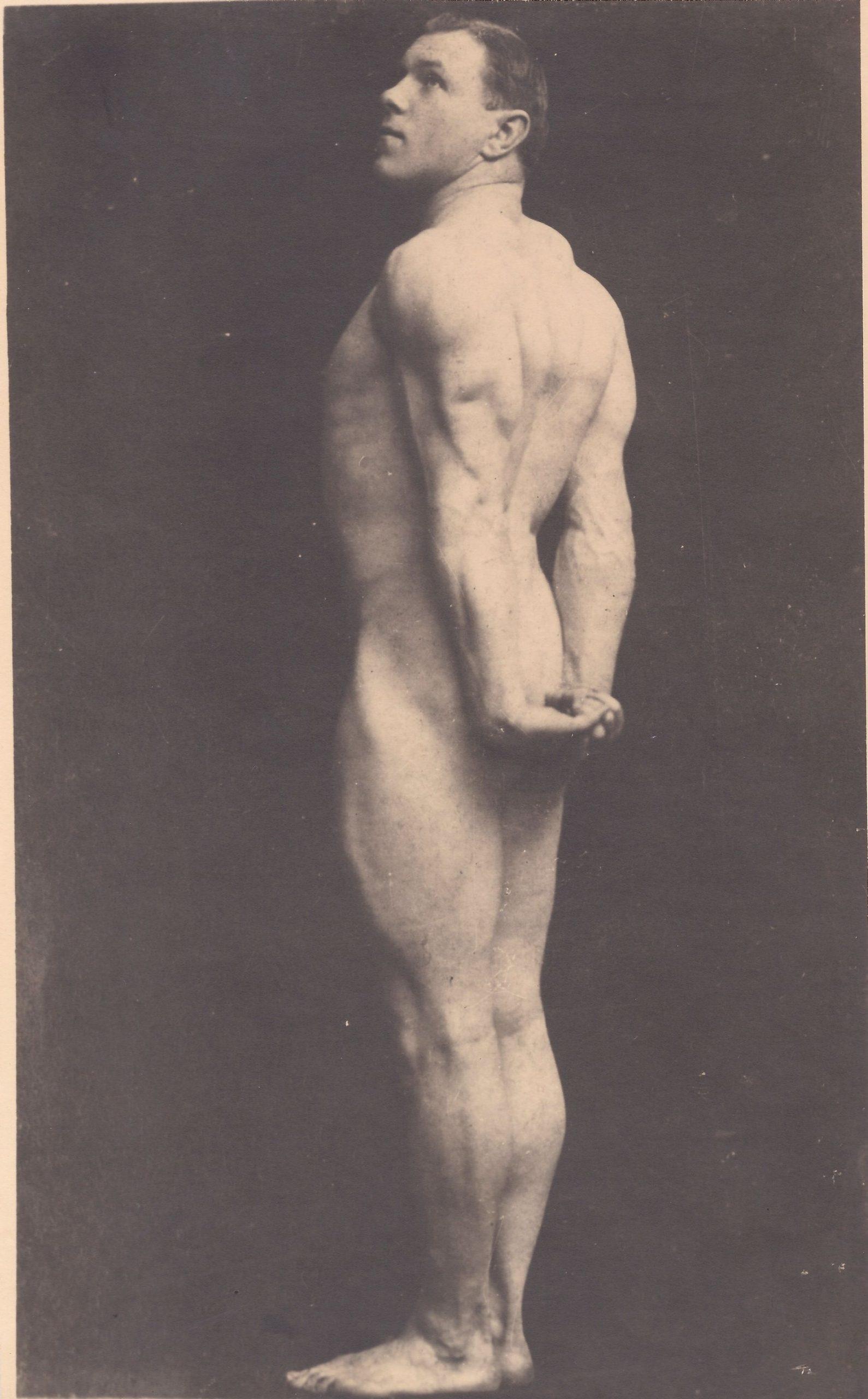

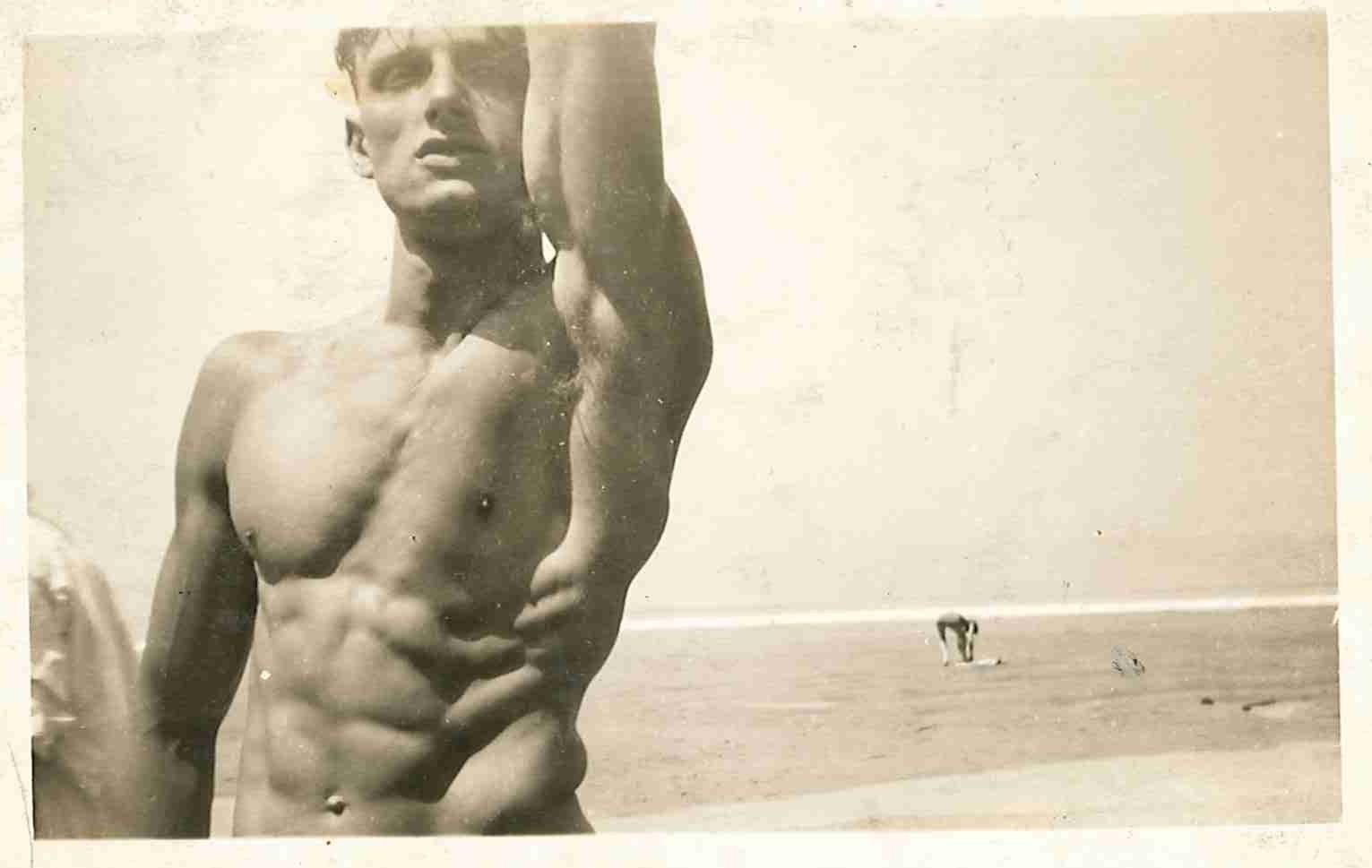

Joe was very complimentary about the relationship we had with Charlie, as well as what Jan and I were doing with our collection at UT, and several years later, in 1985—when he learned we were going to be in England—Joe asked us to visit him and his family. We agreed, of course, and during our few days there we met his wife and his brother and fellow lifter, Charles, who as a young man had been a very popular artists’ model in London. In fact, we spent the better part of a day on a walking tour with Joe and Charles visiting five or six public statues in London for which Charles had served as the model. They also took us to see the grassy spot of unmarked ground in the Putney Vale Cemetery under which lie the remains of Eugen Sandow, whose wife refused to erect a gravestone or marker of any sort.

Joe also surprised us greatly while we were there by giving us almost all of his excellent photo collection as well as a number of other artifacts, and it was during that visit to his modest but exceptionally neat and happy home when I asked him—remembering his stories of having been friends with the Hackenschmidts—when George’s widow, Rachel, had died. “I haven’t seen her for quite some time,” Joe said, “but I don’t believe Rachel is dead. I’m sure I’d have heard of her death from someone.”

Although I knew that Rachel, who was born in France, was at least two decades younger than George, I was astonished by the news and asked Joe if he knew where she lived. “Let’s look in the directory,” Joe said, and lo and behold there was the name “G. Hackenschmidt” listed at the same address where she and George had lived for many years. Next to the name was a number, of course, and when Joe dialed it Rachel answered. Joe then told her briefly about us and offered to bring us to her home so we could pay our respects, and within an hour we were inside a large, handsome home on the walls of which hung two very large prints of photos of George which are known to all serious fans of the iron sport.

Although Rachel was then in her early 90s and mostly confined to her bed she seemed very pleased to see Joe again. Her memory was still sharp and we spent an hour or so talking about George’s career, their difficult lives during the two World Wars, their home in France, and their many friendships. She also wanted to hear more about the collection we were building at the University of Texas, and after we’d told her what we were trying to do she looked at Jan and at me and at Joe and said something which left us all speechless. She said that she was very happy that Joe had brought us to see her because she had been worrying about what to do with the things she had had since George’s death in 1968. She went on to say that she thought he would be happy to know that his materials had gone to a place where such things were kept and where they could be studied and enjoyed by others. Well…

She then directed us to a nearby room and a bookcase there, where we found two large scrapbooks filled with photos and clippings, four over-size prints like the one we’d seen on the wall, several copies of George’s books, a box of manuscripts, and other related items. Taken together, these artifacts—and especially the huge scrapbook of clippings—were breathtaking to see and to hold, especially as Jan and I and even Joe had been unaware of their existence. Joe and the two of us looked at some of the clippings and photos with Rachel, and when we left carrying this remarkable trove she was smiling. She seemed genuinely satisfied that what she called “George’s things”–which she had guarded during the years since her beloved George had passed away–were going to a place where they would be used by scholars and preserved for future generations.

In the many years since, we’ve done our best to provide a safe home for these precious items, and to share them with fellow lovers of the iron game, but back when they first came to us we could hardly have imagined that the day would come when the advances of technology and the explosion of the internet would allow us to make it possible for people around the world who still hold Hack in the highest regard to be able to open his largest scrapbook, turn from page to page, and even enlarge any page for easier reading.

Rachel has been dead for many years now and so has Joe and so has Charlie, but they were all pivotal in the series of events which led to George’s scrapbook becoming part of the Todd-McLean Library here at the Stark Center, being digitized, and becoming accessible electronically. Partly because of Charles A. Smith and Joe Assirati, Rachel Hackenschmidt passed George’s remaining materials to us and we, in turn, now pass them on to the world.

Leave a Reply