In 1987, Jan and I acquired from the legendary Sig Klein a number of artifacts which had been in the Klein-Durlacher family for a very long time. Those artifacts included a copper-headed walking cane bearing the name of Professor Attila, which was the professional or “stage” name of Louis Durlacher, who taught Sandow much of what the famous strongman knew about strength and, especially, stagecraft. After he had helped launch Sandow’s career Attila left Europe and settled in North America in 1893. Another “Attila” artifact was a satin-smooth wooden wrist-roller Klein told me the Professor had brought from Europe. Much more significant, of course, was the remarkable scrapbook documenting the Professor’s long and successful career as a strongman and, later, as the owner of what for a time was arguably the most famous gym in the United States. The scrapbook has been scanned in its entirety, and will be made available to visitors to our website within the next couple weeks – check back soon for more information.

Even more significant, in the minds of some iron game experts, was the gilt-framed oil painting of Attila supposedly painted in 1887 by a “court painter” who did portraits of members of the royal family. The story I got from Klein, who got it from the Professor’s widow, was that one or more of the “royals” was grateful to Attila for the work he had done as a personal trainer and so he commissioned a particular court painter to produce a portrait of Attila as a present. In any case, the painting had come down to Klein and his wife (the Professor’s daughter Rose) and it was one of the very few things that Klein didn’t sell when he closed his landmark gym in Manhattan in the mid-1970s.

Ever since we got the painting and the other items from Klein, the Professor has hung in our offices at the University of Texas, and now that we have in the Stark Center a proper art gallery, we wanted him to hang there in the company of paintings of Sandow, Klein, Grimek, Greenstein, Willoughby, and others. The problem with this plan was that the ornate gilt frame was in increasingly fragile condition and the painting itself had had so many coats of varnish through its long life that the Professor’s “complexion” was yellowish/orange and he looked as if he suffered from an advanced case of jaundice. Instead of a medical doctor, however, we carried the Professor to a healer of paintings—Mark Van Gelder, a conservator of art who lives in Austin and does restorations for museums as well as individuals.

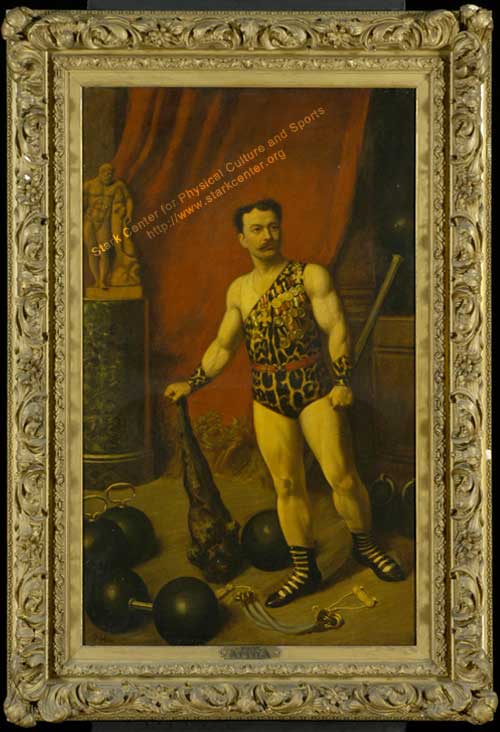

Attila oil painting before restoration

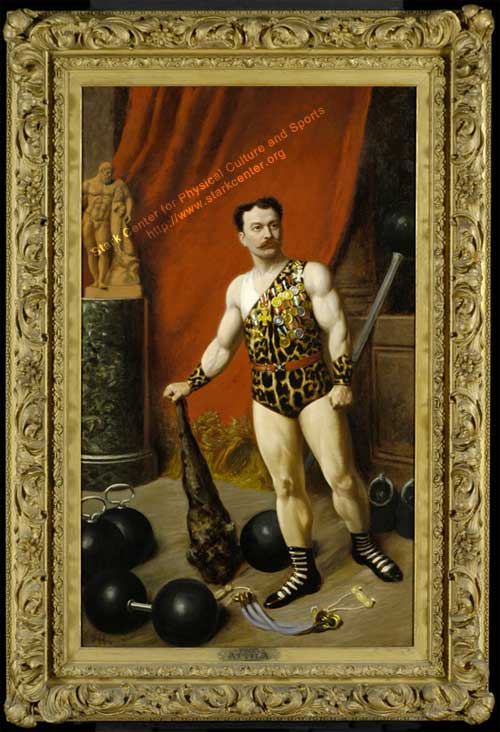

Attila oil painting after restoration

We were nervous, of course, to move the Professor, and we missed being able to see him every day, but we hoped the time and money it took to restore the iron game pioneer would be worth it. You may by now have noticed the photos which accompany this blog, but if you haven’t please pay them some mind; they represent an entirely new version of the old physical culture standby—the “Before and After” shot. Take a look and see what you think. It’s easier for those of us who saw the portrait as it was—dimmed by time, dirt, and varnish—to fully appreciate how dramatic a change Van Gelder’s restoration produced. But even the photos are striking. For example, until the restoration, we didn’t know that at the time the portrait was done the Professor’s moustache was red—not black like his hair. Even his muscles look fuller. And the medals—the medals!—seem almost three-dimensional so brightly do they shine. In time, we intend to have them restored as well since we have most of the ones seen in the portrait and we also intend to have “Doctor” Van Gelder minister to the lesser ills suffered by Grimek, Klein, and Greenstein. For now, all of us at the Center are content to visit the Professor every day in his place of honor in the art gallery and congratulate him on his miraculous recovery.

When I go, I always greet the Professor with one of Kleins’ favorite expressions, “Kraft Heil.”

Leave a Reply